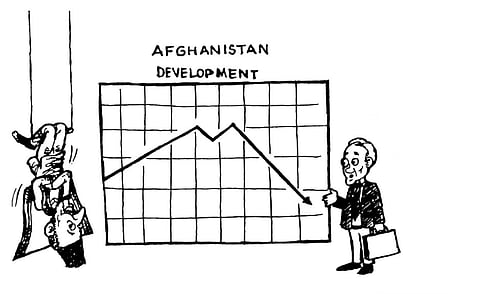

Stunted development

During the last seven years, the US and the international donor community have spent some USD 15 to 31 billion on rebuilding, development and democratisation activities in Afghanistan. Today, the tangible result of this work seems to be the population of some nine million citizens suffering acute food insecurity, and millions of others facing widespread violence, endemic corruption and political anarchy. When asked about the progress made in the past several years, President Hamid Karzai and his Western backers revert to what seems to be a pre-recorded mantra: five million refugees have returned home; over five million children now go to school; an enlightened constitution has been enacted; and elections have taken place, allowing democracy to take root. Meanwhile, few politicians, if any, like to talk about the significant problems that have cropped up in the disbursement of international aid, nor about the widespread corruption and misuse of these funds.

The NGO business has boomed in post-Taliban Afghanistan, greased by the significant inflow of aid money. Hundreds of Afghan and international organisations currently operate in the country, with most of the latter restricting their work to the north and central regions due to the lack of security elsewhere. Yet for all of these eyes ostensibly on the ground, there remain large gaps in basic knowledge. To begin with, neither Kabul nor any one of the Western capitals has a very good idea of how many people actually live in Afghanistan. The lack of a reliable census – due to insecurity and deficiency in funding and other technical support – has not only adversely impacted on development policies (particularly in the planning phases), but also creates confusion in implementation and uncertainty at the national and local levels. Yet the government and the aid agencies nonetheless continue to claim to have improved living conditions for all. Such self-congratulation seems inappropriate because incomplete data makes it impossible to judge the scope and depth of the impact of aid money.