Are we so bankrupt in imagination and inspiration that we are unable to create our own art forms giving expression to our modern way of life with that freedom which is still before us – the freedom which a wise use of the machine as a new and wondrous tool can bestow on us?

– 'Architecture and You', Marg, October, 1946

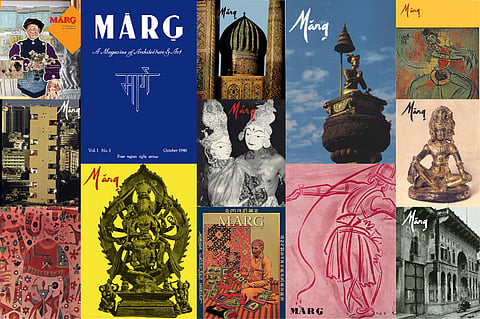

The inaugural edition of Marg magazine, published in October 1946 opened with 'Architecture and You'– a ten-page-long charter boasting of a sui generis format comprising illustrations, floor plans and line drawings interspersed with quotations from Vitruvius and Plato to Frank Lloyd Wright and Francis Yorke. Unbridled in its tone, the manifesto probed into the vacuous sentiment of nationalism in India as a form of "retrogression", an "escape in the absence of our ability to create a national character expressive of ourselves today, in the 20th century." Apportioning an almost cautionary warning against the adoption of an "Indian style of architecture" or "Indian traditional architecture", it described the regular Indian street's medley of hybrid building styles as "spurious antiquity" and "vulgar modernity". Case in point – an illustration of a Taj Mahal-like structure accompanied by a caption scoffingly states, "railway station or Mogul palace"? Invoking rationalism, social justice, and social engineering, the manifesto espoused the notion of architecture as a synthesis of "a structural science and an exact analysis of social needs", vouching for an international modernism as the way forward. Its no-holds-barred approach suggested that our modern way of living has absolutely no relation to the amalgam of architectural styles.

'Railway station or Mogul palace?'

The inception of Marg was inextricably linked to the foundation of a nation on the brink of Independence. Mulk Raj Anand, litterateur, novelist, institution-builder, and social activist – and a leftist – returned to India in 1945 after spending two decades in London and founded Marg in 1946 with 14other founding members.

The magazine soon established itself as one of the country's most well-regarded publications on the built, visual, and performing arts. Its founding members hailed from across the globe: Sri Lankan sisters Anil de Silva and Minnette de Silva (while Anil served as the assistant editor and was also one of the founders of the Indian People's Theatre Association, Minnette, the first woman architect from Sri Lanka, was the architectural editor); German architect and chief architect of Mysore State Otto Konigsberger; Karl Khandalavala, who served as the magazine's art advisor; art historian Hermann Goetz; architects M J P Mistri, J P J Billimoria and Andrew Boyd; John Irwin, who served as the keeper of the Indian section of Bombay's Victoria and Albert Museum; art critic Rudolf von Leyden; poet and art critic Bishnu Dey; Fyaz-ud-din, the first president of the Institute of Town Planners, India; urban planner Percy Marshall; and Shareef Mooloobhoy, a connoisseur of the arts. "Each founder contributed a thousand rupees to start the magazine. It was funded by 300 subscribers and about 25 advertisements in the early issues", shares Rizio Yohannan, publisher of Marg and CEO of the Marg Foundation, a public charitable trust.

The inception of Marg was inextricably linked to the foundation of a nation on the brink of Independence.

MARG (Modern Architectural Research Group) acquired its nomenclature from the eponymous MARS (Modern Architectural Research Society), conceived in Britain in 1933 by architects and architectural critics who were part of the British modernist movement, including Francis Yorke, John Betjemen, Maxwell Fry and Wells Coates. While MARS' utopian socialist credo served as an exemplar for MARG, the magazine concurrently aimed at charting a trajectory that would define and mould the reading of critical histories of art-writing and visual culture. Encapsulating the essence of a recently-decolonised nation, it intended to spread the knowledge of the ancient and contemporary principles of architecture in India and abroad.

Anand challenged various status quo positions in the country; his anti-colonial political beliefs were instrumental in shaping the magazine. In his inaugural editorial 'Planning and Dreaming', Anand maps a schema for a nation on the threshold of independence: "And, planning…does not mean what it is superficially supposed to mean, a mechanised, regimented life. On the contrary, planning is like dreaming – dreaming of a new world." Beholding the figure of the architect as a symbol representing resurgent India, Anand was cognisant of the lack of facilities for training planners and architects, and "very few for training the building operatives and craftsmen on whom their works depend for its execution, and little appreciation by the public of what their work involves". He condemned the hollow glorification of symbols that invoked myopic nationalism, and eschewed the pomp and grandeur of the British imperial strand of architecture.

Most notably, it was the patronage of industrialist J R D Tata that cemented the foundations of Marg. Anand had met him at a luncheon organised by scientist Homi Bhabha. As the former general editor Pratapaditya Pal narrates in Marg's 50th anniversary issue: "After a pleasant meal and listening to Dr Anand's eloquent and valuable presentation, J R D asked, 'What can I do to help?' Dr Anand responded by boldly requesting seven advertisements and the use of two rooms. 'Done', said J R D." While the editorial headquarters of Marg took root in Anand's apartment in Cuffe Parade in southern Bombay, in 1968, the Tatas provided the magazine office space at the Army and Navy Building in the Kala Ghoda precinct, its current location. Until 2015, the same building housed the editorial office of yet another publication – the monthly Freedom First, a now-discontinued journal founded by Minoo Masani in 1952. Its mandate was to ensure "liberty of thought, belief and action and the realisation of economic and social justice for all citizens of the free republic".

Since 2010, Marg has been functioning independently under the Marg Foundation. "The goodwill of influential individuals from various walks of life was one of the factors that helped Mulk give shape to the 'marg' (Sanskrit for 'pathway') that he and his friends in the arts and architecture had dreamt of", says Yohannan.

The making of Mulk Raj Anand

Born in Peshawar in 1905, Anand earned a doctorate in philosophy from University College London. His move to London in 1925 was a consequence of self-imposed exile following his arrest for anti-colonial agitation and participation in the Civil Disobedience Movement in undivided India. It was this time spent in England that inflected his pluralist ethos.

Marg's beginnings in Bombay coincided with the city's emergence as a crucible of artistic potential.

Anand was proactive in labour-led coal-miners' protests in Britain in the mid-1920s and later the anti-fascist struggle during the Spanish Civil War. While in London, he worked with Leonard Woolf at Hogarth Press, as a reviewer for T S Eliot's Criterion magazine, and consorted with writers from the Bloomsbury Group such as Andre Malraux, Bonamy Dobree, and Lawrence Durrell. The city offered him fertile ground to form associations with cultural practitioners that would then accentuate his leanings towards egalitarianism and developing a humanist approach. It was in London that he formed acquaintance with intellectuals like George Orwell, Sigmund Freud, E M Forster, Aldous Huxley, Stephen Spender and Una Marson.

Anand's abhorrence for the conventions of the caste system was manifest in his writings. He was part of the quartet of the foremost Indian writers of fiction in English, the others being Ahmed Ali, Raja Rao, and R K Narayan. He vehemently inveighed against caste and class discrimination that plagued Indian society through a series of novels including his debut Untouchable (1935) followed by Coolie (1936), Two Leaves and a Bud (1937), and The Big Heart (1945).

Mulk Raj Anand in his apartment at Cuffe Parade, Bombay.

In 1935, he co-founded the Marxist-influenced All India Progressive Writers' Association which propelled the standards of criticism of literature towards social realism. Assuming the mantle of Marg's editorship – from 1946 to 1981 – he intended the magazine to be a "loose encyclopaedia of the arts of India and related civilisations", and one where architecture was considered as the "mother art". His perpetuation of art and architecture as powerful liberating tools reflected in his expository editorials.

The exuberance of cosmopolitan Bombay

Marg's beginnings in Bombay coincided with the city's emergence as a crucible of artistic potential. Bombay's cosmopolitanism in the initial years following Independence could perhaps be spoken of the way literary critic Pascale Casanova in her book The World Republic of Letters (1999) spoke of the universality of Paris in the first half of the 20th century. Bombay had arrived on the global map of modernism, as a juncture for creative encounters where subcultures of poets, writers, filmmakers, architects and activists were looking to express themselves and their brand-new freedom. The Urbs Prima in Indis was a fulcrum for cultural production and buoyant expression. Seminal figures who were part of the city's cultural canon included theatre doyen and archivist Ebrahim Alkazi, poet Nissim Ezekiel, screenwriter Khwaja Ahmad Abbas, among many others. The Progressive Artists' Group was conceived a few months after Partition, breaking the yoke of the colonial-influenced academic traditions. Architectural firms led by both Indians and the English proliferated, embracing modern design, thus distancing themselves from the classic Edwardian style of building. Diasporic minorities and migrants were pivotal in moulding the transnational vocabulary of modernism in Bombay. It served as a gateway to transcultural convergences for those who had sought refuge in or exiled to the city, with modernism becoming the exemplar for both dissent and liberation.

Articulations of Nehruvian technocracy

We are on the eve of big development changes in India. Industries are growing up. Community Projects and National Extension Schemes are attacking the static village. In considering these developments, we must always keep in view housing. Any factory, that is planned, should include good housing for all its workers…In the older factories, it would be a good thing if a certain sum was set aside from the profits every year for housing and amenities. This should not be looked upon as a philanthropic gesture, but as something necessary for the social well-being of the people working there and, therefore, for their greater efficiency and effectiveness.

An imminent concern confronting a newly independent India – witness to the ravages of Partition – was that of habitation for its large-scale population. Jawaharlal Nehru believed architecture was necessary to construct a cultural vision for the country. In the new nation-building process, rapid modernisation and mechanisation were upheld as instruments of social change. The building typology embraced by a crop of young Indian architects bore the imprint of their modernist training. It was characterised by open-plan designs, use of materials such as steel and reinforced concrete, liberal fenestration and an assimilation of scale and volume – all harnessing modern technology and the integration of local, natural elements.

At the International Exhibition of Low-Cost Housing in 1953-54 in New Delhi, Nehru enunciated the relevance of the architect, and not merely that of an engineer. Apart from his encouragement towards young Indian architects such as Habib Rahman, Achyut Kanvinde, Shiv Nath Prasad and J K Chowdhury to design buildings for the recently independent country, he was also influential in the appointment of Charles Edouard Jeanneret-Gris (or Le Corbusier) to plan and design the upcoming capital city of Chandigarh, along with engaging Jane Drew, Maxwell Fry and Pierre Jeanneret.

Anand determinedly rejected the thought of reviving past traditional styles to define India's post-Independence architecture. However, in an edition of Marg from 1949, Sri Lankan architect Andrew Boyd exercised a caveat:

Boyd went on to express that an entire city of modern architecture would be "wearisome" and "inhuman", a typology that was intended for a small circle of the refined ruling class and not the masses. A tightrope walk between the search for a new Indian modernity and holding on to the vestiges of tradition was unfolding in the pages of Marg.

The magazine's voice largely grew out of Anand's personality and beliefs. He upheld social justice; aligned to Nehruvian ideology, Anand looked in retrospect at pre-colonial Indian art to lend legitimacy to the formation of an inchoate nation, and forward to the unfolding of a rational, humanist state. Often referred to as a "book-magazine", each edition of Marg offered a comprehensive discourse on a particular subject.

Jyotindra Jain and Latika Gupta, who served as editor and associate editor of the magazine respectively from 2015 to mid-2020, state:

Entire issues were dedicated to the disquisition on the arts of Bhutan, Burma, Cambodia and Sri Lanka, as well as editions on the painting traditions of Nepal, early art from Thailand, and the heritage of Samarkand. Even as the magazine's coverage was anchored in a bricolage of the many shared cultural and colonial histories of the subcontinent, it recurrently addressed civic issues.

December, 1961 edition on Chandigarh.

Through the late 1950s and early 1960s, Marg carried articles – an entire edition even – on the Chandigarh plan, evaluated and examined by both architects and critics. The experiments of Le Corbusier and his collaborators were documented and analysed extensively, encompassing the city's housing, gardens, public buildings, and industrial structures. In June 1965, it was in the pages of Marg that architect Charles Correa, along with Pravina Mehta and Shirish Patel, first presented a radical proposal that paved the way for the "dream city" of New Bombay. The plan would equipoise the extant city's crumbling, overcrowded north-south axis to an east-west one across the harbour. While it did enable the creation of what is today known as the twin city of Navi Mumbai, the Vasantrao Naik-led government, in 1970, did not exactly accept it the way it was proposed.

Apart from the lack of fervour among readers for architecture-centric issues, the newly emerging architects in the 1960s focused more on practice than engaging in architectural writing or discourse.

While he was the Chairman of the Lalit Kala Akademi, Anand initiated India's first Triennale of Contemporary World Art in 1968, an idea that was regrettably consigned to oblivion as a result of its inability to build successive editions. Held in New Delhi, the works displayed were from more than 30 countries. A pictorial catalogue of sculptural works, organised nation-wise, was published in the March 1968 edition of Marg.

"Mulk's ideas evolved over the years. The sense of what the magazine wanted to achieve had gradually shifted to nation-building from public intellectual culture, and also became a way to place India on an international platform. It kind of gave an image of the nation as culturally proud and publicly secular – that is what modernism represents," shares art historian and designer Annapurna Garimella, who also edited Mulk Raj Anand: Shaping the Indian Modern (2005), a commemorative volume on Anand's contribution to the visual and built arts. In her essay 'On Inheriting the Past', Garimella discusses Anand's way for the presentation of regional heritages:

Several issues of Marg focused on identifying, documenting and analysing the arts and heritage. These thematic monographs unravelled monuments and sites such as the temples of Khajuraho, the caves of Bhimbhetka and Bagh, dargahs in northern India, and provided insights into the archaeological relevance of Mahabalipuram and Hampi. Entire editions were devoted to subjects such as Buddhist art, Manipuri dance and Pahari murals. Even as the magazine sought to strengthen regional identities, it did so without resorting to regional chauvinism. Its internationalism was perhaps reflected through its March 1971 issue dedicated to the monuments in Bamiyan. Enabled by the governments of India and Afghanistan, the effort was to not only document but also restore and conserve the monuments. Moreover, Marg backed artist Akbar Padamsee during his arrest and subsequent court case in 1954, for his failure to remove two paintings that were considered "offensive" during his exhibition in Bombay. The judgment, which favoured Padamsee, was published in the magazine. Yohannan states that:

While the magazine took a more Indological bent during the editorship of Pratapaditya Pal (1993-2012), it did not recoil from addressing issues of social and cultural gravity. In an essay titled 'Jangarh Singh Shyam and the Great Machine' (December 2001), art historian Kavita Singh underlined the hapless situation of the exploitation of the extremely talented Gond artist by institutions abroad. Shyam is believed to have died by suicide in July 2001 whilst at an art residency at the Mithila Museum in Japan. Singh's article called for an urgent response to his untimely death, thus attempting to safeguard the interests of other artists in the future.

The imposition of the Emergency on 25 June 1975 saw an outpouring of resistance from artists, authors and cultural practitioners across the country. They participated in movements against the Emergency, leading to their imminent detention and arrest. Channelling discontent, poets and writers discreetly brought out pamphlets and newsletters against the government, later distributed by student volunteers. While street theatre came to be used as a tool for dissent and open rebellion, the Delhi-based Jana Natya Manch (popularly known as Janam) led by playwright and activist Safdar Hashmi – founded in 1973 – was silenced. Documentary filmmaker Anand Patwardhan, who was then filming the rising support for Jayprakash Narayan across the country, went underground. Films were censored and the media was muzzled. While several artists, activists and intellectuals condemned the Emergency and the punitive restrictions that curtailed freedom of expression, Marg conceivably failed to highlight the zeitgeist of this turbulent moment in history in the immediate wake of its occurrence. The magazine seems to have shied away from re-emphasising the value of democracy, or highlighting the significance of dissent in the arts. Freedom First, in fact, shut for six months during 1975-76 instead of submitting to pre-censorship. Filing a petition with the Bombay High Court, it successfully challenged the censorship order [Binod Rao Vs M R Masani, 78 (1975) Bom LR 125].

Entire issues were dedicated to the disquisition on the arts of Bhutan, Burma, Cambodia and Sri Lanka, as well as editions on the painting traditions of Nepal, early art from Thailand, and the heritage of Samarkand.

In a similar vein, the killing of Safdar Hashmi during the performance of Halla Bol on 1 January 1989 by a mob led by a Congress leader in Jhandapur – and the widespread protests it galvanised – did not see an immediate response from Marg. It was only later in 2018 in an article titled 'Modes of Resistance in India: Sahmat's experiments in dissent' by Ram Rahman that Sahmat's canon of using art as an instrument to critique and resist rightwing politics, its association with the Indian People's Theatre Association, and the protests against the demolition of the Babri Masjid in the early 1990s was highlighted, particularly in the aftermath of the brutal killings of radical thinkers such as Gauri Lankesh, Govind Pansare, M M Kalburgi and Narendra Dabholkar. With the two aforementioned examples, Marg perhaps became more reactive than proactive in its editorial approach.

In 1996, Charles Correa headed a study group appointed by the Maharashtra government to propose a plausible alternative to the redevelopment of the swathes of mill land in Mumbai – a plan that would regulate commercial development with the intention of benefitting the city dwellers. When the Supreme Court had irrevocably withdrawn the stay granted by the Bombay High Court on the sale of the mill land, there was no legal remedy left. It was, however, important for the citizens to realise the repercussions of the ruling. Radhika Sabavala, who served as general manager at Marg from 1992 to 2018, says:

In the post-Anand years, Marg's focus became more art historical but in no way flippant. "It was pathbreaking in its own way. One must also understand that the times had changed. When Mulk started Marg, India wasn't even born, so his editorial mandate was all about a new nation, setting new standards, and starting right from the building bricks", explains Sabavala.

Dwindling architecture coverage?

While Marg was ardent about the larger space of art and culture since its beginnings, its coverage of architecture – one of the foundational buttresses of the publication – had evidently dwindled from the late 1950s. The remarkable heyday when architecture held substantial space in its pages had begun to slowly fade. "Mulk was quite self-reflexive; by academic training he was a philosopher – and that might have helped him gain a distance and reflect on what was ailing Marg," says Yohannan. In an editorial for the magazine's December 1963 edition, Anand expressed how it had failed to generate the movement it had wished for:

Apart from the lack of fervour among readers for architecture-centric issues, the newly emerging architects in the 1960s focused more on practice than engaging in architectural writing or discourse. This is also perhaps palpable from an abrupt decline in the quality of writing in journals such as Design, The Indian Builder (both founded by political commentator and publisher Patwant Singh) and Journal of the Indian Institute of Architects in the course of the coming years.

Marg's coverage of projects concerning housing for the urban middle class had also become less robust. In a paper titled Marg Magazine: A Tryst with Architectural Modernity the authors Kathleen James-Chakraborty and Rachel Lee highlight:

Furthermore, the initial sanguinity of the new nation state, especially seen through the lens of its architecture, had begun to abate. The rise of Floor Space Index (FSI) rather than local planning by-laws had thwarted the fabric of many urban precincts that were the hallmark of architecture from the 1930s to the 1950s. The Nehru-Mahalanobis strategy built on a model developed by Russian economist G A Feldman was not without its flaws. India had lost a war to China; the country had lost its longest-serving prime minister by 1964.

More than public involvement, Marg brought about public awareness. Through the later years of Mulk's editorship and afterwards, Marg came to be known more for its art historical and scholarly publications. "Importantly, Marg was intended as a magazine that had a life and critical value beyond the quarter it was published. Hence, there was a clear editorial view to keep it distinct from current-affairs magazines that are aplenty in the market, as are magazines that focus specifically on contemporary urban artists and gallery exhibitions", explain Jain and Gupta.

In 2015 – under the editorship of Jyotindra Jain and Naman Ahuja – Marg's commitment to becoming more responsive to the times, and equally committed to bring out original, rigorous research, deepened. The magazine was envisioned to provide analytical essays that critically examined the entanglements of 'culture' with social, political and economic realities, in line with the transformations in disciplinary approaches that expanded from 'traditional art histories' into cultural studies. "We underscored the notion that art and culture were not independent entities as such but were in fact socially and politically constructed. In this, we maintained a balance between turning the focus to 'ancient' and 'medieval' art/architecture/visual culture and that of the modern and contemporary, in line with Marg's vision of critical scholarship that cuts across historical periods and geographies", share Jain and Gupta.

Even as the magazine sought to strengthen regional identities, it did so without resorting to regional chauvinism.

The magazine's editorial approach veered away from individual opinion-style pieces to champion multi- and inter-disciplinary approaches. According to Jain and Gupta, these approaches "unpacked cultural themes through critical lenses, bringing fresh insights and excellent scholarship out of the domain of academics to a larger reading public, in accessible language but without being populist or buckling under fleeting trends."

For instance, the issue titled 'Documentary Now' (September 2018), guest-edited by Ravi Vasudevan, revisits the archive of documentary films in India, simultaneously exploring their contemporary history with a focus on Yugantar (India's first feminist film collective), and also reflecting upon a politically-charged Assam of the 1990s – the epicentre of the The United Liberation Front of Asom (ULFA) separatist movement – through the lens of Mukul Haloi's 2017 film Loralir Sadhukota (Tales from Childhood). The volume 'Staging Change: Theatre in India' (March 2019) evaluates state institutions that help locate where cultural policies (or the lack thereof) stand today. "Additionally, the issue addresses the Armed Forces Special Powers Act (AFSPA); the relationship between the 'mainland' and states like Assam and Manipur through the work being done in theatre; and other chapters look at the location of gender and caste", share Jain and Gupta. In 'The Draw of the Hills' (June 2018), perspectives range from understanding place, regional identity and tourism discourses in Ladakh drawn on the distinction made between 'space' and 'place' by social geographers to the pitfalls of corporate takeover of heritage management and conservation.

Marg September, 2020 issue

Since 2020, Marg's charting of a fresh path is apparent from its new format, designed to serve the twin purposes of consciously creating a broad-based, persuasive tone while being serious-minded. "[The magazine's] architecture allows plurality of scope and intensity of exploration at once. A magazine that can shape a cultural discourse for our times and one that has a legacy to engage with all facets of art and culture – we saw Marg's future in evolving ourselves to become that marg for India, Southasia, and the world at large", says Yohannan.

In 2018, Marg launched its digital archive, supported by the Tata Trusts. Besides increasing engagement with audiences via social media, the magazine has also begun a series of online conversations under the rubric of 'Marg Salon', with recordings made available free of cost. Yohannan concludes, "We see the significance of 'architecture' which Mulk referred to as [the] 'mother art'. For a writer like him, it was a metaphor for building a people on their organic cultural base. That way, in 2020, this 'marg' indeed seems to have come full circle".