Those who deny that caste is really much of a 'problem' should look at the case of Chitralekha. She is a Dalit (Pulaya caste) woman in Payannur in Kerala, married to an Other Backward Caste man. In 2003, she decided to take up the profession of autorickshaw driving (as her husband does), since the nursing course she was in training for required night work, which would have impeded on her ability to care for her children. Since then, she has been constantly harassed by the 'caste Hindus' who dominate the Communist Party of India (Marxist) autorickshaw union. Her autorickshaw was torched; then a new one was also ruined by having salt poured into its gas tank. Finally, she herself was beaten by a mob working with the police. When we talked to the aggressive members of the union in the local CPM office, they refused to even recognise Chitralekha's marriage, calling her a "woman who lives outside the tracks". After all, she and husband, Sheeshkant, had committed what the 'sacred books' call varna-samkara, mixture of castes.

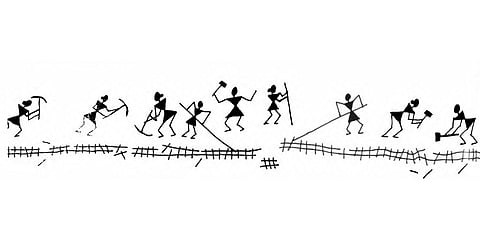

Outside the tracks? The tracks are those that bear the still-very-alive caste system in India. The train that runs on those tracks is a gloomy one, driven by the power of the Vedas, the Manusmriti, even the Gita. At its head is the Brahmin engine, followed by other of the sacred 'twice-born'. Behind, without much power to influence its running, swung along by the wily engine, are the Shudra carriages – divided from one another for, as B R Ambedkar noted, "Caste is not a division of labour, it is a division of labourers." Different Shudra jatis are not supposed to intermarry or 'inter-dine', and even today violations of these codes evoke penalties in many of India's villages. The caboose is that of the Dalits, tagging along at the end. Running at the side, perhaps, can be said to be the Adivasis, the marginalised, with Brahmin hands reaching out to drag them along with the train. And sitting in every carriage, often with curtains around them, with inferior food and sleeping space and clothing, are the women of each caste.

Today, there are those who not only want to get off the train, but to derail it completely. Perhaps the victory appears distant; yet the inequality and turmoil in modern-day India are unprecedented. Indians bring caste along with them wherever they go in the world, and the debates and conflicts have continued in England, the US, the Gulf and elsewhere. In the first two, the tradition of civil rights has added support to the battle against the caste train.

Just recently, in a victory for the 'subalterns', the British Parliament, which considers racism a crime, voted to treat caste as part of race. It had been a long struggle – with a group called the Hindu Council UK lobbying, though a wordy report, that caste was really not a problem, that it had originally been equalitarian, that calling Shudras "as the legs" (which the Rig Veda does) had to be read in the context of legs being part of the body and essential to it; and that, anyway, caste was dying. In short, the Council rehashed all of the tired old arguments, which can also be found today on countless 'Hindu' websites. But in the end, the arguments of justice triumphed in England. Of course, caste and untouchability are outlawed in India, too. The difference is that countries such as Britain enforce their laws.

We want to derail the train, tear up the tracks. There are still Gandhians today who argue that 'caste', with its supposed virtues of solidarity, can be maintained without the hierarchy and oppression. This is impossible. What would a caste-free India look like? Enough intermarriage, for one thing, so that everyone would have to admit that they come from many 'caste' backgrounds. There would be openings everywhere according to talent, not the supposed 'merit' type that belong to those with millennia of superior backgrounds. There would be no identifiable 'caste quarters' in villages. Perhaps names might remain – after all, the US and England have Smiths, Carpenters, Potters – but in India, as there, no one would remember that they mean anything.

~ Gail Omvedt is Dr Ambedkar Chair for Social Change and Development at the Indira Gandhi National Open University, New Delhi.