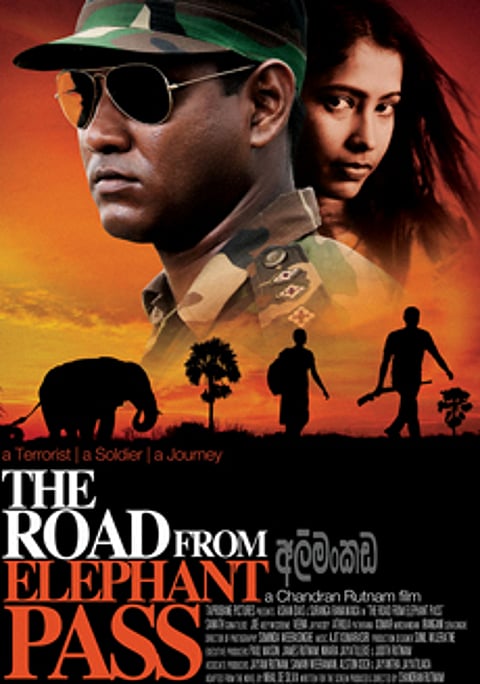

A rocky road: ‘The Road from Elephant Pass’ directed by Chandran Rutnam

Elephant Pass is the narrow strip of land connecting the island landmass of Sri Lanka to its northern Jaffna Peninsula. Bordered on left and right by lagoons and marshes, this isthmus carries both the main A9 Highway and the railway line connecting Jaffna to the rest of the country. In the nearly 30-year civil war between the LTTE and state security forces, the Jaffna Peninsula was of keen strategic importance for both sides, and control over this vital link has been fought over on at least two modern occasions. During the course of its struggle to establish a Tamil homeland in the north and east, the LTTE first attempted to capture the Elephant Pass military camp in 1991, but was thwarted. Its second attempt, however, in April 2000, was brutally successful, and was considered the biggest debacle suffered by the Sri Lankan forces at the time. The LTTE proceeded to hold the territory until the final phase of the war, when the Sri Lankan forces recaptured rebel areas and eventually eliminated its top leadership, including its leader, Velupillai Prabhakaran.

Sri Lankan feature films based around the civil war have been few and far between since the conflict began in the early 1980s. In 2001, the human-rights activist Sunila Abeysekera noted that it was "quite remarkable" that contemporary Sri Lankan cinema had "failed to deal with critical moments in the history of the island that have led to sometimes violent social and political upheaval". For Abeysekera, the "most critical silence and absence" was "that relating to the ethnic conflict and the subsequent state of civil war in the country". Despite Sri Lanka's claims to being a multi-ethnic and multi-religious country, its cinema, says Abeysekera, is exclusively in Sinhala and "represents and reproduces the lives and concerns of the majority Sinhala-speaking people of the island. In the context of a history of discrimination and marginalization of minority communities … this absence could also be considered as part of the same process of erasure."