The Rhetoric of Relevance and the Graveyard of Gandhi

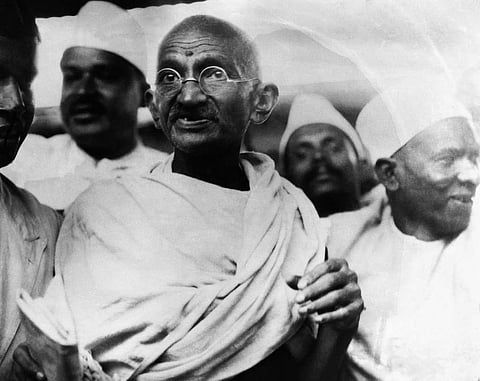

As the anniversary of Gandhi's death approaches, the tired old question of Gandhi's 'relevance' will be rehashed in the press. Once we are past the common rituals, we are certain to hear that the spiral of violence in which much of the world seems to be caught demonstrates Gandhi's continuing 'relevance'. Barack Obama's ascendancy to the Presidency of the United States furnishes one of the latest iterations of the globalising tendencies of the Gandhian narrative. Unlike his predecessor, who flaunted his disdain for reading, Obama is said to have a passion for books; and Gandhi's autobiography has been described as occupying a prominent place in the reading that has shaped the country's first African American President. Obama gravitated from "Change We Can Believe In" to "Change We Need", but in either case the slogan is reminiscent of the saying with which Gandhi's name is firmly, indeed irrevocably, attached: "We Must Become the Change We Want To See In the World." Obama's Nobel Prize Lecture twice invoked Gandhi, if only to rehearse some familiar clichés – among them, the argument, which is so seemingly infallible that it has been seldom scrutinized, that Gandhian nonviolence only succeeded because his foes were the gentlemanly English rather than Nazi brutes or Stalinist thugs.

Let me, however, leave aside for the present both the question of Obama's Gandhi and the liberal's Gandhi, and turn rather briefly to some more general problems in the consideration of Gandhi's place in world history. The Gandhi that is known around the world, and to a substantial degree even in India, is principally the architect and supreme practitioner of the idea of mass nonviolent resistance and the prime example of the 'man of peace'. The general sentiment underlying this view is clear enough, even if one thought of bringing to the fore evident objections to such a characterization of Gandhi. One might argue, as some historians have, that the role of Gandhian nonviolence in the achievement of Indian independence has been overstated, or one could adopt the view, a more nuanced and interesting one, that 'peace' was not particularly part of the vocabulary with which he operated. The centrality of ahimsa (nonviolence) and satya (truth) to Gandhi's way of thinking aside, if one had to add another set of terms that might signify his practices and thought alike, then one would perforce think of brahmacharya (celibacy, closeness to God), tapasya (sacrifice, self-suffering), aparigraha (non-possession), and so on. Though silence was an integral part of his spiritual and political discipline, Gandhi studiously avoided speaking of shanti (peace). One of the many reasons he did so is that peace has all too often been used as the pretext to wage war. Describing the barbarous conduct of the Romans some 2,000 years ago, the historian Caius Tacitus put it rather aptly: 'They make solitude [desert] and call it peace'. I suspect, moreover, that if Gandhi had been alive to see how he has been packaged, sold, and denuded of all insights and vitality by the practitioners of what are called 'peace studies', he would have been rather pleased at his insistence on nonviolent resistance rather than on peace.