Beauty and contradiction in Tibetan art

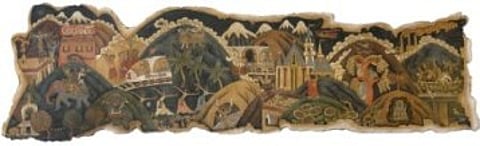

I first met the Tibetan artist Gadé (transliterated as dga' bde) on a cold November day in 1994. After showing me around the Fine Arts Department of Tibet University, where he was working as a lecturer, we looked at some of his own art works. His paintings were enthralling. Some depicted elegantly posed figures swathed in warm colours, while others were of delicate bodies framed within the silhouette of a resting Buddha. Gadé uses paints he makes from mixing different types of minerals, and his work therefore carried an earth-tone colour scheme, occasionally accentuated with bright hues. Buddhist symbols imbued his works with a sense of serene beauty and mystery.

A few hours later, over lunch at a newly opened Indian restaurant on Beijing East Road, Gadé said that a Chinese postage stamp was being released that featured one of his paintings, a rare opportunity for a Tibetan artist living in Tibet. The restaurant at which we were eating was owned by two businessmen, one Tibetan and one Nepali – it is one of the joint-ventures that has boosted the economy and the mood of Lhasa residents following the years of particularly repressive control. The novelty of being able to eat spiced curries while watching Tibetan girls wrapped in colourful saris dance to Indian music had made the restaurant, for a short while, the talk of the town. In a way, the restaurant represented Lhasa and Gadé – hybrids made of a mixture of Tibetan, Southasian, Chinese and Western influences.