Bridge-Building and Baglung’s Blacksmiths

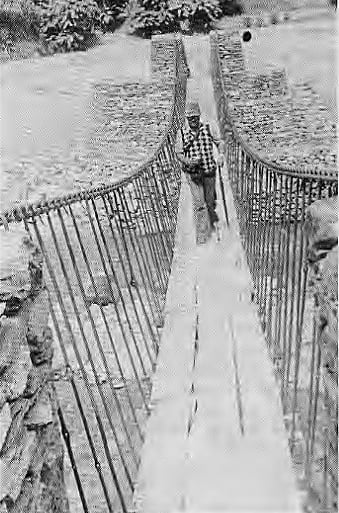

There was a time when, with great craftsmanship and skill, the village people of Nepal built their own bridges. Temporary spans were built with bamboo ropes, twisted vines and matted fibers, and lasted through the rainy season. Permanent suspension bridges were built by local blacksmiths, kamis, who used local ore to build strong iron chains which were linked together to span gorges more than 250 feet wide. With intuitive knowledge, and without help of surveyors and engineers, the villagers would choose the spot where the river cuts the steepest, where the banks were stable. The indigenous chain link bridges used no mortar or cement, and required no tempered steel cables manufactured abroad.

Ironically, this tradition of indigenous engineering started to disappear when the Government began to take an interest in bridge building. The decline began when Rana Prime Minister Chandra Shumshere, who ruled from 1901 to 1928, first imported bridges from Aberdeen, Scotland. The first "government" bridge was built in 1907 in Khurkot over the Sunkosi River, between Sindhuli and Ramechhap districts, east of Kathmandu. (The flood of 1985, destroyed this bridge.)

When foreign aid began to flow in the 1960s, the Government and foreign donors began to look at bridge building with renewed interest. They were guided by the development reports of Toni Hagen, the well known geologist and United Nations consultant, who trekked all over Nepal from 1953 to 1959. Yet, by his own admission, Hagen was all too ready to apply to Nepal the standards of his native Switzerland.

A sensitive advisor like Hagen, honoured by then Premier B.P. Koirala as "a gifted observer and patient analyst," had failed to comprehend the appropriateness of the centuries old, chain-link suspension bridges that stood so proudly and visibly, in the gorges of the midland mountains. Despite these total neglect in the rush to erect modern suspension structures, several of these old chain bridges are still standing, testimony to their durability and safety, and to the craftsmanship of the villagers who built them. These traditional bridges have served the mountain people longer and better than recent highways, STOL airstrips and modern suspension bridges. And yet, they are denigrated as "inferior" and "primitive." Over the past three decades, as expensive but quickly fabricated western imports replaced locally built bridges, the indigenous craft of centuries was allowed to go rusty – except in Baglung in central Nepal, where the people did not forget.

"Learn From Baglung"

In the 1960s and 1970s, western-educated Nepali engineers and American and Swiss advisors erected 43 "modern" bridges. Between 1975 and 1978, the people of Baglung built 62 traditional bridges. The Baglung bridges cost only NRs 10,000 on the average, not counting the free labour provided by the villagers. The bridges ranged from 30 feet to 300 feet in length, and were deemed safe by the engineers who studied them.

While indigenous bridges were built elsewhere in Nepal too, Baglung's was the only instance of a large scale bridge building programme organised by the local people. Donor agencies such as UNDP, SATA, USAID and the US Peace Corps were impressed enough to send delegations to discover Baglung's secret. "Learn from Baglung" became the unofficial development slogan for a while.

Despite the usual professional reluctance to "learn" from villagers, the Baglung experience was so forceful that it helped reorient the nation's bridge building programme. Kathmandu engineers introduced some changes to the Baglung design and named these hybrids "suspended bridges," which were technically simpler than modern suspension bridges and more quickly constructed. The introduction of suspended bridges led to a spurt in construction. While, only 61 bridges were built by the Government between 1975 and 1980, 301 bridges were thrown across Himalayan streams and rivers between 1980 and 1985.

However, even the modified traditional designs were ultimately inferior to the original chain link bridges. They needed tempered steel cables from Japan or Switzerland, and were slower to build, with no guarantee of longevity. Unlike the native suspension bridges, they too required expensive concrete foundations, struts and beams of steel, and the cost of carrying cables to the bridge site was enormous, something like NRs l0 per kilogram per day in the Pokhara area.

On the other hand, the Baglung blacksmiths used local labour, local smelting techniques and designs to provide a local service. Their work did not require foreign consultants or foreign aid. So, Government paper-pushers and engineers had little to do, and there were no opportunities for bridge inauguration parties to be flown in from Kathmandu, at a cost equal to that of the bridges themselves.

The Honeymoon Is Over

After a brief honeymoon with the suspended bridge, the national bridge building programme once again got bogged down and the chain link bridge faded further in memory. Of the 53 suspension bridges which should have been built last year, only 19 were completed. Even so, the bridges that are built have had a high "mortality rate." Of the 11 suspension bridges built by the American aided Resource Conservation and Utilisation Project (RCUP), during the past five years in the Kali Gandaki valley, "nine are already in the Bay of Bengal," said one engineer, who was recently in the area.

In the end, neither the Nepali experts nor their foreign advisors could accept the notion that the "primitive" blacksmiths of Balgung knew their ropes and cables better than they. If the 1970s slogan was "Learn from Baglung," the 1980s cry might well be "whoever heard of Baglung?"

***

How the Majority Travels

Transportation for the majority Nepali hill population does not mean riding on the roof of a bus, nor, swooping down from the blue unto a STOL airstrip. It means strenuous walking over foot-trails from the road head, with heavy loads of kerosene, salt or cereals on heaving backs. According to one estimate, more than 3 million hill dwellers are on the move over the Nepali trails at any one time during the trading season from October to May.

Even a small upgrading of the trail means much more to the hill dweller than the highways he will admire but never use, or the buzz of Royal Nepal Airlines turbo-prop engines, high overhead. If you ask the district administrator or the local merchant for a Dasain wish-list, he will say "highway" or "hawaijahaj." If you ask the peasant, he or she will ask for a safer and broader foot-trail and a suspension bridge, to shorten the portaging distance. Even if the administrator and the merchant have not, the villager has realised the hollowness of the 1960s slogan, "development follows roads."

(For a detailed discussion of portering, see the July 1988 Himal.)

~P.C. Joshi is a civil engineer and Anil Chitrakar a mechanical engineer. They are interested in the use of appropriate technology to alleviate hill poverty.