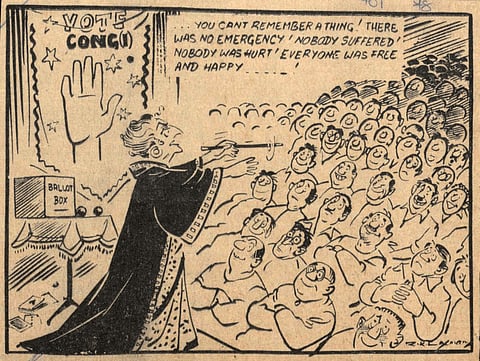

The ‘good-governance’ problem

M G Abrol was presumably asleep in his house when, in the early hours of 21 March 1977, the noise of a telephone rang through the halls. The additional secretary in the Ministry of Finance might not have been surprised to hear the voice of his equivalent at the Ministry of Home Affairs, P P Nayyar, at 2.30 am in the morning. For the past twenty months, India had been under Emergency, with the prime minister's executive-rule filling the vacuum left by the suspension of democracy. It was a period replete with late-night calls and secret lists being compiled by bureaucrats for penalising dissenters, sometimes on the instructions of political functionaries, sometimes in sheer caprice.

Only, Nayyar had called to inform him that the Emergency had been withdrawn. Abrol recounted that fateful conversation in a 'Secret Note' penned on that day: