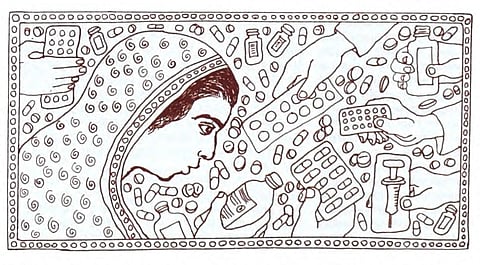

Drugs for the people

Bangladesh's endeavour to establish a comprehensive drug policy dates back to 1972, when a committee of experts, lead by the renowned physician Dr Nurul Islam, first proposed the banning of hazardous and useless drugs. However, the committee lacked support from key sectors of the government and was soon dismantled. This was not surprising, given that in the 1970s through the early 1980s, the pharmaceutical market in Bangladesh was dominated by just a few multinational companies, including Squibb, Wyeth Laboratories, SmithKline, Pfizer and Eli Lilly. Together, the foreign companies controlled more than 75 percent of the market, and supplied most of the essential drugs to the government, at very high prices. Additional ramifications of this industry composition included the flooding of the market with dangerous and unnecessary drugs, including vitamins, tonics, enzymes, gripe waters, cough mixtures, restoratives and digestants. A market survey in 1978 reported that harmful and pointless drugs accounted for a full third of the total drug consumption in the country.

After a decade of disquiet over this toxic situation, pushed by academics, regulatory experts and health activists, Bangladesh implemented the National Drug Policy (NDP) in 1982. It aimed to ensure quality and, importantly, to expand the domestic drugs industry. Yet the new policy received an immediate and hostile response from domestic and multinational pharmaceutical companies alike, as well as associations of local health professionals and certain foreign governments, including the US, Britain, West Germany and the Netherlands. These parties argued that the new policy would discourage foreign investors, would result in more harm than good for public health, and would not achieve the goal of increased availability of medicines. For their part, the multinationals further warned that the policy could result in a decision to halt all pharmaceutical production by foreign companies, with devastating impact. Within two months, although the Dhaka government persisted with the main thrust of its drug policy, some changes were introduced in response to this pressure. These included permitting some banned products back on the market, extending the time period for implementation of regulation, introducing an appeals process, and altering the list of permitted products.