The limited genius of Geoffrey Bawa

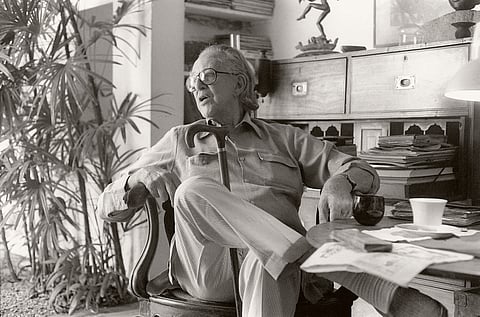

Just before 1948 – the year Ceylon gained its independence from the British – and before he earned his great renown, the Sri Lankan architect Geoffrey Bawa, upon his return from Europe, bought an abandoned rubber plantation in Bentota, a coastal town in the Southern Province of what is now Sri Lanka. Over the course of four decades, Bawa transformed it into the sprawling Lunuganga estate of today. The place is named after the brackish Dedduwa Lake upon which the estate rests – the words Lunu–Ganga denote salt-river. Michael Ondaatje, the Booker Prize-winning Sri Lanka-born Canadian writer and a friend of Bawa before the architect's death, has claimed, "If we wish to see a self-portrait of Geoffrey Bawa we will find it most clearly in his own garden and home in Lunuganga." Bawa was infamously reticent about his work and life, and Lunuganga serves as a manifesto of sorts of his architectural vision. Bawa himself, in Lunuganga – a volume he co-authored with the Swiss architect Cristoph Bon and the Sri Lankan photographer Dominic Sansoni – describes the estate as a "garden within a garden". The larger garden being Sri Lanka itself.

Lunuganga was imagined as a space outside, a "sanctuary" which borders on society, remaining both inside and outside the secular, material world. The garden at Lunuganga is lush, excessive, and decadent. Yet at the same time, it is ordered by a carefully thought-out spatial arrangement, with classical sentries and balustrades that frame and add perspective to the natural flow of the garden. There is a subtle and nuanced interplay between order and freedom. The beauty of Lunuganga emerges from this dialectic; to deploy a Nietzschean metaphor, it seems to strike a perfect harmony between the opposing Apollonian and Dionysian forces. The eclectic design of Lunuganga reflects a melange of architectural traditions. Austere Palladianism with gothic details seamlessly merged with local architectural features in a tangibly modernist architectural diction. This, arguably, "postmodernist" pastiche-like approach to architecture defines much of Bawa's work. Yet it is at Lunuganga where Bawa seems to have unleashed the full creative force of his vision.