Languages and labour on tea estates in South India and Sri Lanka

This article is part of Dialectical, a Himal series that explores Southasia’s languages, their connections and shared histories. Part one of this article on the languages of tea estates in Southasia can be read here.

In the late 19th century, coffee plantations first in Ceylon and then in mainland India were swept by a fungal epidemic. The disease was called coffee leaf rust, and caused the slow and inevitable death of coffee plants. British planters detected the disease by 1869 and tried in vain to counter it with fertilisers and labour-intensive cures, but these achieved only partial success. By the late 1870s, commercial coffee production in Ceylon, started by the Dutch around the 1780s, had steadily declined, and the resulting crisis was exacerbated by plummeting demand for coffee from Southasia as cheap Brazilian coffee flooded the British market and Britain entered a general economic depression. With crashing prices and yields, Ceylon’s coffee cultivation collapsed by 1886 – disastrous news for a crown colony reliant on cash-crop exports.

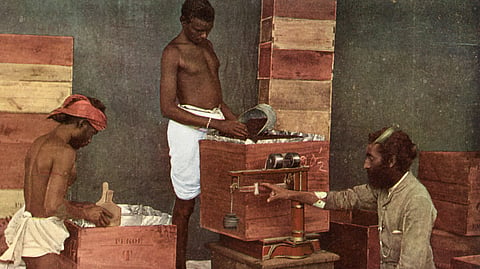

Building on earlier Dutch trials, the British expansion of coffee plantations – driven by European capital and South Indian labour – had transformed the Ceylonese economy by the 1850s. Coffee monoculture, and a focus on exporting only coffee, dominated from 1840 to 1875. Fuelled largely by commercial interest, in the wake of the coffee crash, the British in Ceylon looked for an alternative. They didn’t have to look far: Tea was already being cultivated in the region on a small scale.

Helped by the switch in Ceylon’s main export, tea quickly replaced coffee as England’s preferred beverage, and the tea trade became the economic backbone of the British colonies by 1890. The entrenchment of tea estates in Ceylon, with their massive need for labour, led to the migration and settlement of Indian Tamil labourers in the highlands of what is now Sri Lanka.

In South India, tea had taken root earlier. In the early 19th century, as the East India Company focused on cultivating tea in Assam, Alexander Turnbull Christie, a young surgeon with the Madras medical establishment endeavoured to introduce tea plants to the Nilgiri range, in what was then the Madras Province. Although Christie passed away before tea saplings could arrive here from southwestern China, they were eventually planted by the colonial officer Richard Crewe at an experimental farm in Kétti village. These plants lay neglected until the French governor of Pondicherry took possession of the farm and entrusted its upkeep to the Swiss-French botanist Georges Samuel Perrottet. Perrottet was instrumental in reviving these tea plants, and ultimately in the establishment of tea plantations in the Nilgiri hills.

The Nilgiri hills are located at the trijunction of what is now northwestern Tamil Nadu, southern Karnataka and eastern Kerala. “Nilgiri” is an anglicisation of nīlagiri, or blue mountains, a Tamil word of Sanskrit origin composed of nīla (blue) and giri (mountain). The name is typically linked to the “blue” mist of these hills or the seasonal blue and purple strobilanthes plants that thrive here.

One of the earliest tea plantations in South India, which came to be known as Coonoor Tea Estate, was established in the Nilgiri hills in the mid 1850s by Henry Mann. Not far away from these hills, tea plantations also took root in Munnar and Wayanad of Kerala. In 1898, two planters from Ceylon helped establish the Stanmore tea estate in the Annamalai hills of Coimbatore district, in Tamil Nadu, further expanding the crops’ footprint in South India. Other prominent tea-growing regions in South India today are spread across much of Kerala, Karnataka and Tamil Nadu.

Like in Ceylon, the expansion of tea estates in South India also demanded a large supply of labour, which was drawn from various sources. The same applies to tea estates across Southasia, including the north of the Subcontinent, which as a result have long been significant sites of linguistic contact and interaction. Tea estates brought together speakers of diverse languages, facilitating sustained and complex multilingual encounters (as I explored in an earlier article). They have fostered the emergence of new lingua francas, which in turn have helped create new social and political networks. However, the expansion of the tea industry has also exerted considerable pressure on minority and indigenous languages, often contributing to their decline.

This piece focuses on the sociolinguistic dynamics of tea estates in southern India and Sri Lanka. It highlights both indigenous languages and the contemporary language practices shaped by the tea industry in these areas, and the experiences of the people living and working on these estates – a part of the story that is often sorely missing in discussions about the expansion of tea cultivation in the Subcontinent.

On the highermost reaches of the Nilgiris lived the Todas, who were solely buffalo pastoralists. They traded buffalo milk and other dairy products with their neighbours. India’s 2011 Census places their population at around 2000 people. Todas speak Toda, a South Dravidian language belonging to the same linguistic sub-family as Tamil, Kannada, Malayalam and Tulu. According to UNESCO’s Atlas of the World’s Languages in Danger, Toda is among the critically endangered languages of Southasia, along with its neighbouring languages Kota, Betta Kurumba and Bellari. Toda is unique in that it has the highest number of vowels and consonants among all Dravidian languages.