The year 1982 was an exciting one for Indian people. The radio and the newspapers were full of news of the Asian Games in New Delhi. Coins featuring Appu, the dancing elephant and mascot of the Games, and the Jantar Mantar in Delhi, about which many of us learnt for the first time, were already in circulation months before the opening ceremony. Newspapers told us that thousands of trees were felled in Delhi to broaden the streets, and that the price of tomatoes there was only INR 2 per kilogram due to the heavy influx of vegetables in preparation for the event. News of the construction of Appu Ghar, India's first amusement park, got kids thrilled beyond belief.

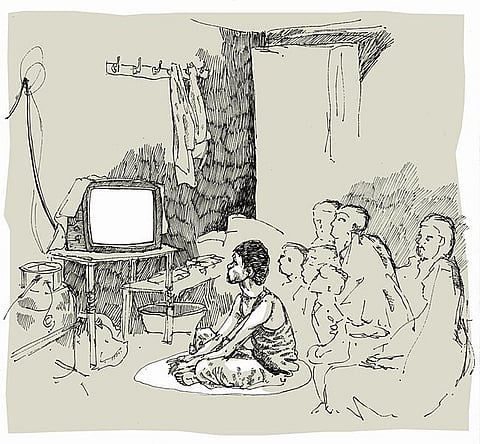

1982 was also the year in which Doordarshan (DD), then the sole television broadcaster in India, started broadcasting its programmes nationally. And with this, television came to Guwahati, the state capital of Assam. The advent of television brought unbelievable excitement. For those with relatives in Guhawati affluent enough to afford a television set, it was customary to explain in great detail to the rest of us how a TV worked and how exciting it was to watch TV programmmes. Most of us developed an inferiority complex, and with extreme jealousy we cursed ourselves for living in such a small town where we were deprived of television's wonders.