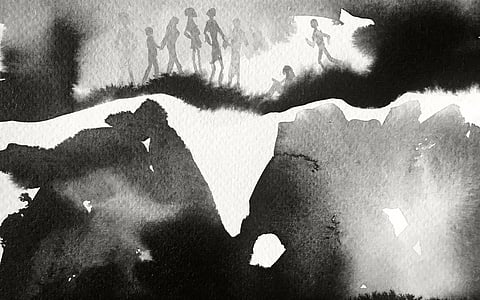

It is autumn and the sky is the colour of smoke. I am sitting by the window, thinking of a land where the women sheathe their hair in henna until it shines like glowing embers in the warm sun of the fall. I wonder if your hair is that same red sheen. But I have sat too long, stared too much, thought too little. It is time I write. This is a letter to you, Swara Bhaskar.

A letter is a false confession. There are secrets in between the lines that make up its opening, middle and end. But these are secrets made up, lives wholly imagined and put into words that make sense only to the sender and receiver. Letters intercepted are like sheets of code, emotions encapsulated in lines. Letters make writers, readers and thinkers but they also make liars out of us.