Excuse me, Milords

The tussle between the judicial, executive and legislative branches is an old one. Competing loyalties, political interference and plain corruption have challenged the independence of the judiciary in most countries of Southasia. Yet when General Pervez Musharraf removed Chief Justice Iftikhar Muhammad Chaudhry for "misuse of office" on 9 March, he probably did not expect the groundswell of protest that was to follow. Demonstrations soon spread from lawyers and the media to human-rights activists and the general public.

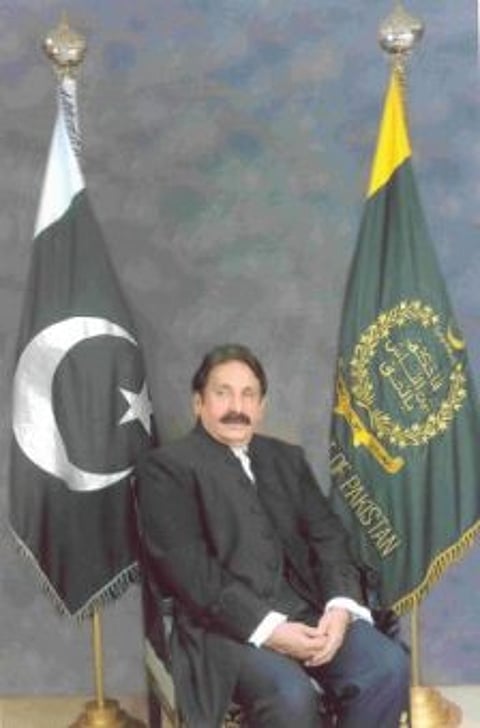

The ousted chief justice quickly became a veritable symbol of resistance to executive high handedness. This was particularly so because the dismissal came in the wake of Chief Justice Chaudhry having taken up cases that Islamabad would rather have swept under the judicial carpet: disappearances (the polite term for those abducted and probably killed by the military intelligence agencies), and the high-level corruption in the Pakistan Steel Mills case. There can be no disagreement on enhancing judicial accountability, but such an obviously politically motivated move is less about keeping the judiciary under the scanner than about removing a chief justice who refused to be a puppet (so goes the received wisdom in Pakistan). The attack on Pakistan's judiciary – and the attempt to control independent institutions – must be viewed with alarm, particularly given the general elections announced for later this year.