Stranded in Geneva Camp

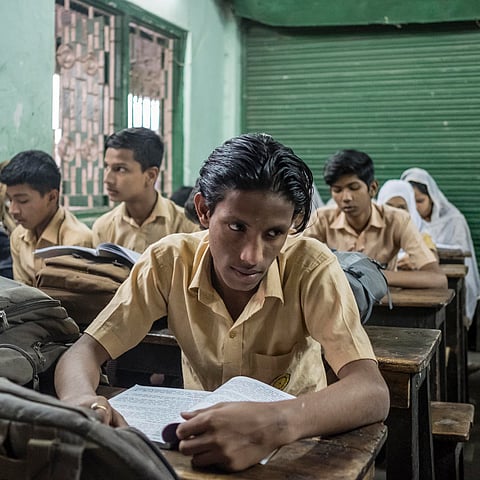

During the swearing-in of North Dhaka's new mayor and councillors in March 2019, Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina mentioned that her government was "looking for land to build flats for the trapped Biharis so they too can live decently." Hasina was referring to the country's Urdu-speaking community of approximately 300,000 people. This community is largely made up of peopled descended from refugees who sought sanctuary in Muslim-majority East Bengal during Partition, coming mostly from Bihar, West Bengal as well as other parts of the subcontinent. Today, most of Bangladesh's 'Biharis' are living in over 60 refugee camps scattered across the country.

During the 1971 Bangladesh Liberation War, a section of the Urdu-speaking population supported the West Pakistan army. As a result, the community was left stranded and stateless in the newly independent state of Bangladesh, and face discrimination for their perceived allegiance to Pakistan, although many of them today were born and raised in Bangladesh. Organisations representing 'Biharis' in Bangladesh have at various times demanded their repatriation to Pakistan. Between 1974 and 1992, around 175,000 'Biharis' were relocated to Pakistan. In 2008, a Supreme Court decision, granted the right to Bangladeshi citizenship to 'Biharis' who were either minors during the Liberation War or born afterwards, then slightly less than half the population. The other half of the community continue to remain stateless.