Girls in the shadow

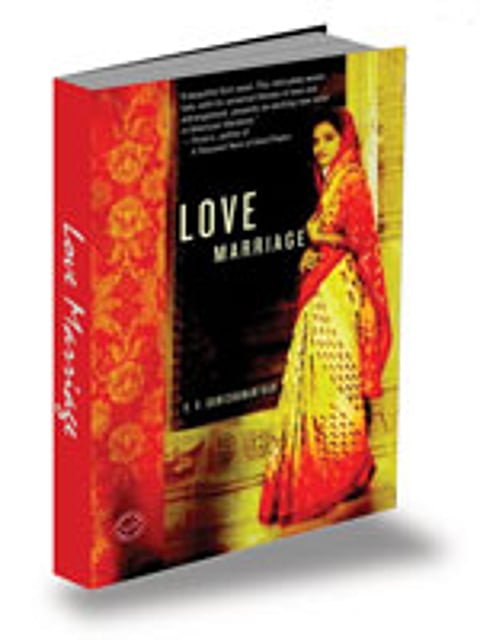

Love Marriage is not in this vein. It is a precious little book, written first as an undergraduate thesis under the direction of the brilliant American writer, Jamaica Kincaid. The story is about a young woman who is detained from her undergraduate studies to help her parents tend to a mysterious uncle and his daughter. It is in such waiting rooms in one's life that one finds out not only about one's past (from the uncle), but also what one is ultimately made of. Indeed, how we deal with such pauses are often better tests of character than how we deal with the inexorable rush of our daily lives.

Evening is the Whole Day, on the other hand, has its pretensions, from a preoccupation with brand names to an almost claustrophobic set of character sketches in search of a plot (which comes very late in the book). There is also an uncle here, although he comes to move things along rather than to act as an anchor for the novel. The story is about a family in stasis, waiting for the elder daughter, Uma, to leave for college, and waiting for the servant, Chellam, to be sent off home for allegedly hastening the death of the grandmother.