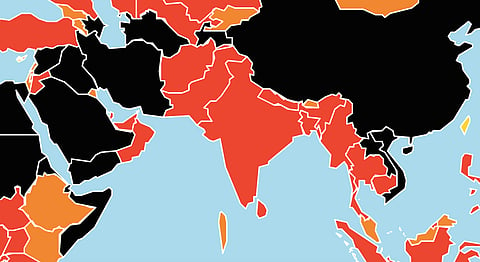

Photo: Reporters Without Borders. (Scroll down for RSF's press-freedom index of countries in Southasia.)

Comment

How free is the media in Southasia?

Governments are finding new ways to silence the press thanks to COVID-19.

On 3 May 2020, the world marked World Press Freedom Day under the shadow of the COVID-19 outbreak. With a large part of the world under lockdown, journalists have improvised and tried different mediums to tell their stories. Meanwhile, in the guise of responding to the crisis, governments have found new opportunities to restrict journalistic freedoms, as well as free speech in general.

In Southasia, such restrictions have come in many forms, from controls on news gathering and expression, to legal harassment, arbitrary arrests and physical violence. In almost all instances, this has been done without legally invoking emergency-time regulations.