Himal Southasian May 1992 print issue

Cover

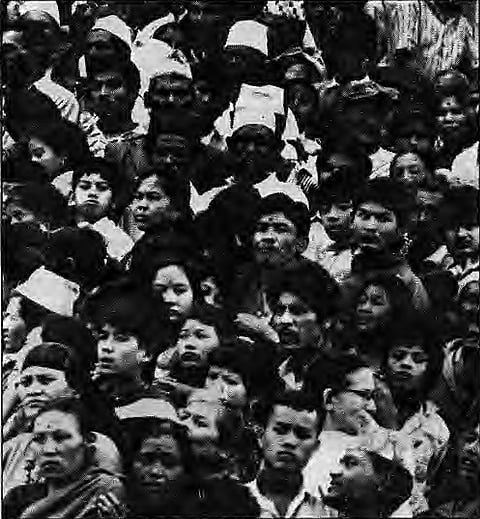

How to tend this garden?

Some 200 years ago, the Gorkha king politically unified Nepal through conquest While the political entity called Nepal has existed all these years, however, the nation state of Nepal has not yet stood the test of national integration. Having been propped up for two centuries by feudal and authoritarian rule, the country is now asked to hold together under a multi-party democracy.

Today, whether they fully realise it or not, those who would rule Nepal are weighed down by the responsibility of managing multi-ethnic, multi-linguistic and multi-tribal divisions. Like elsewhere in the young and emergent states of Asia and Africa, the search is on for a single cultural identity that would make Nepal a "nation-state" rather than merely a "state".