India-Pakistan roadblocks to regional peace

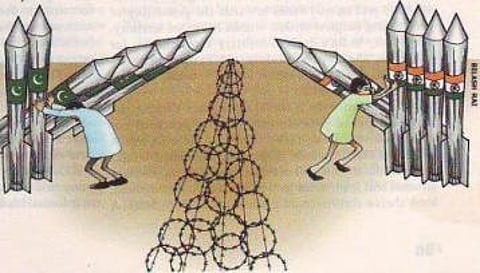

India's remarkable macro-economic turnaround since the early 1990s has put it on the pat to global recognition. Yet several incisive commentators have noted in recent times that the country continues to be held back from realising its true potential because of unresolved political tensions with its neighbours, especially with Pakistan, the second largest player in the region. Indeed, India's relationship with Pakistan has largely come to shape the geopolitics of the region as a whole. Given the overbearing size of the two economies and their military strengths, these two countries alone largely dictate the extent of integration possible within the region as a whole. It is therefore no surprise that persistent hostilities between New Delhi and Islamabad over nearly six decades have left Southasia as economically one of the least integrated regions across the globe.

That the future of the Southasian region largely depends on the course India-Pakistan relations end up taking is a given. The utmost importance being accorded to the ongoing peace process is therefore warranted; but there is also the suggestion that a successful end to the peace bid would automatically lead to complete 'normalisation' of relations. The two 'automatic' outcomes suggested are a move away from high military expenditures and enhanced economic ties, with the latter also providing ready means for enhancing people-to-people contact.