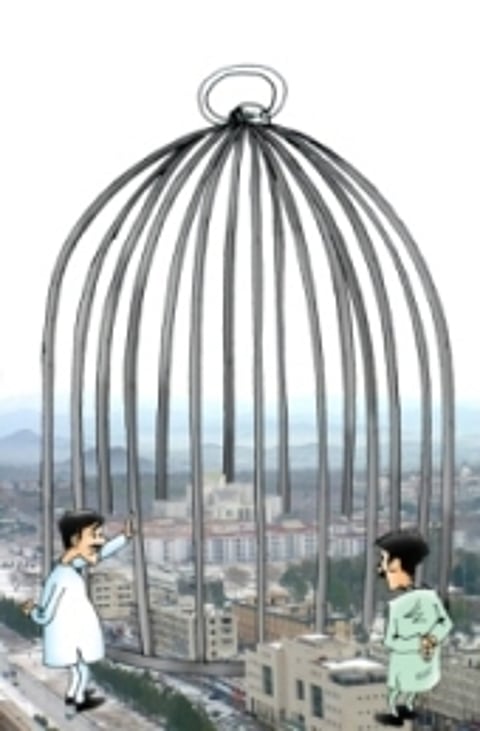

Islamabad’s gilded cage

Since late January, the sleepy, custom-built capital of Pakistan has seen a spate of suicide bombings. What was once the safest haven in a conflict-prone political and social zone is now besieged with security forces patrolling the streets, forcing residents of this gilded cage to own up to the reality that suddenly exists within its own borders.

On 26 January, a suicide bomber walked into a staff entrance of the Marriott Hotel in Islamabad, was intercepted by a security guard, and blew up them both. I was inside the hotel when the blast occurred, cocooned within its opulent surroundings. Had the blast occurred minutes later, I would have been crossing the street in the midst of the carnage. This fortuitous timing did not stop me from witnessing bits of charred flesh lying scattered on the road, however, as I ran out to join the crowd that had gathered. This was the first suicide bombing to have taken place in Islamabad.