Lhotshampa, Madhesi, Nepamul: The deprived of Bhutan, Nepal and India

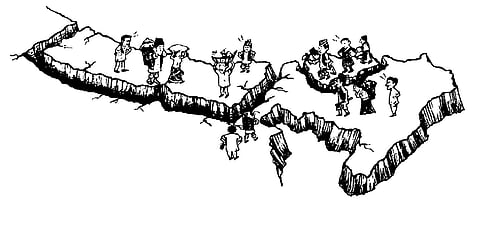

The thin stretch of land from Dehradun eastwards to Arunachal Pradesh, variously identified as the bhabar, tarai or duar, is today much in the news, particularly in the Nepal context. But just a century and a half ago, this was not known as a densely populated area. Only a few ethnic groups and stray settlers populated this land, infamous for flash floods, wild animals and, especially, malaria. Today, however, these resource-rich plains of Nepal, Bhutan and India have turned into a hotbed of dissent – an area of continued neglect and exploitation, often ignored by decision-makers, and largely circumvented by nation-building efforts. Uncovering various aspects of deprivation inevitably leads to the lost opportunities of three significant communities: the Madhesis, the Lhotshampa and what can be referred to as the nepamul bharatiya, or Indian citizens of Nepali origin.

In Nepal, it is usually claimed that those today referred to as Madhesis are the land-hungry migrants from the Indian plains who came to the Tarai after the so-called Sepoy Mutiny of 1857, purportedly with a view to clearing the area's forests and occupying its fertile agricultural lands. For their part, in India it is similarly maintained that, around the same time, Nepalis were invited by the British to develop Darjeeling and to mine copper and mint coins in Sikkim. Finally, in Bhutan the claim is that the Lhotshampa were recent illegal migrants to the country. Yet there is sufficient historical evidence to show that the ancestors of the Madhesis in the Tarai, the Nepamul in Sikkim and Darjeeling, and the Lhotshampa in Bhutan were already in these areas well before the 1814-15 Anglo-Nepali war. Indeed, not only should these groups not be called 'migrants', but some of them have good claim to be considered sons and daughters of the soil.