That night, Indra Bahadur could not sleep. In the orange streetlight that came through the window, he studied his lottery stub; the red boxes for the numbers 4, 7, 2 and 8 were shaded carefully. Those were numbers given to him upon registration in Kathmandu – after the physical check, the endurance test, the run up a 600-metre-steep hill with forty kilos of rocks in a basket. 4-7-2-8. His name for fifteen years in the Singapore Police Force. He had arrived in the newly independent Lion City as a young Gurkha recruit with tender blisters from his first pair of boots. The Sikh regiment had packed their bags to go home after Indian Independence and the Nepalis now took their place. After all, the Gurkhas were known for their bravery. They fought the British with just their khukuri knives. Indra remembered feeling like a fraud when he first arrived. He had been nothing more than a farmer's son in far-western Nepal. His family worked, harvested, and ate.

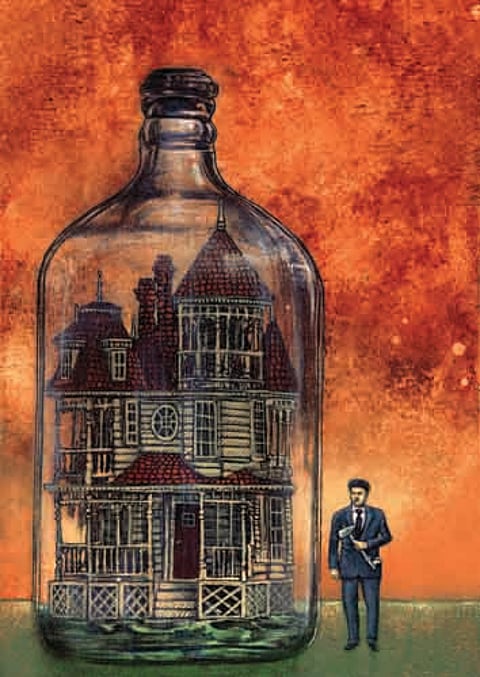

And here he was on this night, wide awake with Subha sleeping beside him, her wrist across her forehead, and Joon their eight-year-old sprawled in between them, her hair plastered, sweat wet on her cheeks. 4-7-2-8. He wasn't too old, he wasn't too young; he was just the right age for a Gurkha soldier before becoming unable to serve. So, Indra was retiring and going back to Nepal but he wasn't just moving back to his village, he was going to settle in the capital instead, the big city where only the wealthy could build homes. He hadn't moved that far up in the ranks since he was still living in a small apartment in Block S where most families lived. Although he had dreamed of living in Block T, he knew that whatever little he was making in Singapore translated to a lot in Kathmandu. Indra had secured a large piece of land in Lazimpat where he could build a house out of imported brick and cement, and bring his mother to the city. His home would have many guestrooms so that people from his village could stay a night or two and experience the luxuries of his life. The kitchen would be separate from the dining room and the living room. And of course there would be a prayer room for Indra's mother and Subha. Maybe even a small car. A car! Who would have thought that a barefooted boy from the west could afford to dream of cars? That he could drive in style and not have to push through people and pickpockets for a damp seat on the three-wheelers and minivans of Kathmandu. He would still have to be careful of thieves; he'd heard that conmen often disguised as pilgrims and donation collectors looted homes. He would have to get a dog, he thought, a big dog. He would make a sign outside his gate: "BEWARE OF DOG", in red. But there were also stories of robbers hurling poisoned pieces of meat at guard dogs to lure them away from the gate. What then? He would have to build bigger walls, a taller gate, maybe even find a gatekeeper like they have at the Camp. Could he afford someone like that? It sure would prove to everyone that he had done well abroad. The gatekeeper would open the door when he drove his shiny car, he would interrogate strangers, and take messages if they were not home.