Memories of Galwan Valley

In mid-June 2020, month-long simmering tensions along the restive border between India and China came to a head with clashes between soldiers in Galwan Valley in the Ladakh region. This resulted in the death of at least 20 Indian soldiers and unconfirmed Chinese casualties. A lot of the media coverage around the incident carried references to the India-China war of 1962. In the weeks since the Galwan Valley incident, social media was flooded with images of people from the Northeast, especially Assam, who were particularly affected by the war in 1962. What is it that makes this border so contentious and restive for these two nation states? The history can be traced back at least 200 years.

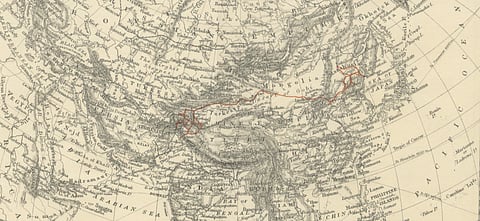

The demarcation of borders and the creation of frontier zones was a major colonial project of the 19th century. Frontierisation was not just a project of the British Empire but also of other colonial powers such as Tsarist Russia and Imperial China, which marked the borders of their colonies for national security reasons. The area around the Galwan River has been perhaps one of the most interesting spaces of transnationalism since ancient times. It was part of an ancient trade route, but since colonial times also the site of border control between three major empires – Chinese, British and Russian. In the 19th century, these three imperial powers scrambled to mark their territories and tried to stop their opponents from transgressing into their own land. As a method of control, the British also started denoting some of these contentious areas as 'spheres of influence.' These were regions where the border was yet to be fully ratified and so were not governed by any single law or authority. The recent military skirmish in the Galwan River Valley has historical parallels to events that date back to the 19th century.