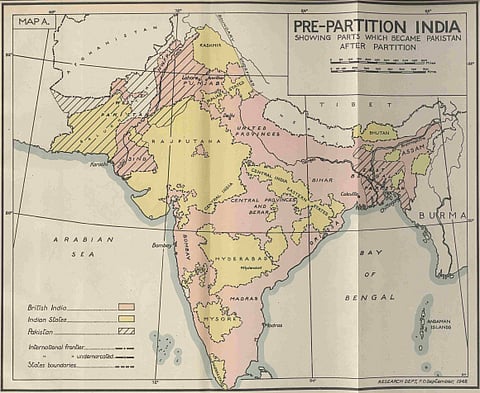

Map of India taken from Report on the last Viceroyalty, Rear-Admiral The Earl Mountbatten of Burma, 22 March to 15 August 1947. Photo: The British Library

Essay

Nations out of fantasy

Modern Southasia’s ‘cartographic anxiety’ is traceable directly to colonial-era machinations. It is time for the region’s people to make their own decisions about how to define their territories.

What the map cuts up, the story cuts across.

– Michel De Certeau

That myths construct nations has by now become a post-truism. In the 60 years since August 1947, most Southasians have realised, and perhaps begun to move beyond, this maxim. The Partition of the Subcontinent and the Independence of India and Pakistan inaugurated both triumph and tragedy in such callous proximity that the story of one remains incomplete – and, in fact, becomes misleading – without the mournful narration of the other.