The politics of democratic planning in postcolonial India

On 29 February 1956, presenting his budget speech as the finance minister, C D Deshmukh said that the Indian people stood on "the threshold of a golden age." The Second Five-Year Plan, with its deliberate focus on industrial production and self-reliance, was to usher in this golden age. The financial journalist Geoffrey Tyson, writing for an April 1956 issue of the BBC weekly The Listener, stressed that the success of the Second Five-Year Plan within the framework of parliamentary democracy was vital for the free world. In India, he went on to say, planning "occupies people's minds in the way that a royal marriage or league football might in other countries."

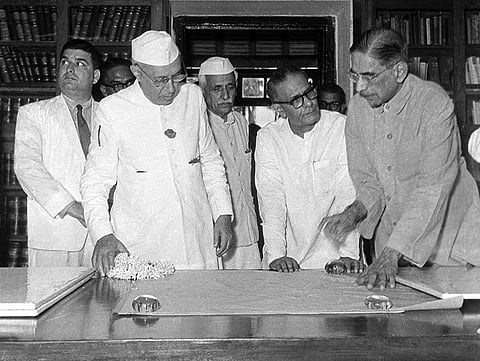

Nikhil Menon's Planning Democracy is a stellar history of planning and its constitutive role in the making and legitimisation of the Indian state. Planning was by no means a new concept or worldview to the founders of the Indian republic in 1947. It had captivated socialist-minded Indian nationalists since the 1930s, culminating in the foundation of the National Planning Committee in 1938 with Jawaharlal Nehru as its chairman. In British India, one of the basic preconditions of national planning – national independence – could never be met. Yet, planning helped the nationalists articulate a vision of a united and free India (including the princely states) that would undo the damage of centuries of colonial spoliation. Menon's book tells us in vivid detail the actualisation of the nationalist vision of planning in the aftermath of Independence.