The poetics of a holy death

His death in Benares

Won't save the assassin

From certain hell,

Any more than a dip

In the Ganges will send

Frogs – or you – to paradise.

My home, says Kabir,

Is where there's no day, no night,

And no holy book in sight

To squat on our lives.

–Kabir, translation by Arvind Krishna Mehrotra

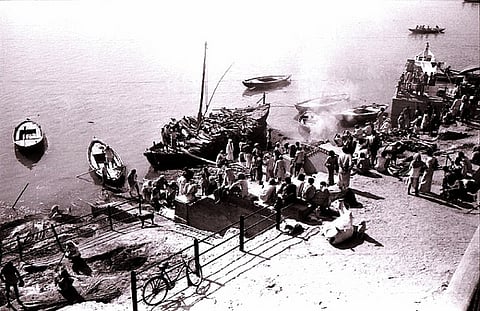

These lines from Kabir's poem 'His Death in Benaras' reflect the pluralist heritage of the holy city of Benaras. Poets and philosophers have long been enticed by the glory of this ancient city, recognising the creative force lurking behind death. Death and Benaras go hand in hand, but with death also comes life. Mythological literature shows that these binary forces sometimes coalesce. In the medieval past and in contemporary times, many poets with diverse views on religiosity have been attracted to the composite culture of Benaras. Akbar, the 'secular' Mughal ruler, patronised the city's progress and it was under him that brocade textiles (known today as Benarasi textiles) found syncretism. His court was also a nucleus of Persian litterateurs, like Abul Fazl, who propagated the syncretic religion Din-i-illahi (Persian for 'divine faith') through accounts like the Akbarnama.

Mosques and temples

Today, what remains in the collective memory of most Indians is the pro-Hindu project of 'Modern Varanasi' under the Rajput, Maratha and neighbouring kings who were religiously inclined towards Hinduism. They ruled during the British colonial times and were involved in tussles over ownership of the sacred city. The British gave the city its anglicised name, and also sought to homogenise the spiritual cults of Paganism, Hinduism, Islam, Buddhism and Jainism. Madhuri Desai, in her essay 'Mosques, Temples, and Orientalists: Hegemonic Imaginations in Banaras', points out many examples that made Benaras an indisputably 'Hindu' city. Taking her cue from Partha Chatterjee's The Nation and its Fragments, Desai elaborates on colonial understandings of the material and spiritual. The inner domain, as colonial scholars understood it, was spiritual and defined by one's cultural identity. With the emergent hegemonic nationalism after the partition of Bengal and the rise of the Swadeshi movement, an urgency was felt to protect spaces associated with spirituality. To symbolise this fervour of nationalism, Benaras began to be represented as a site of "unalloyed Hindu spirituality".