In Bangladesh, a centrist reset and an Islamist breakthrough

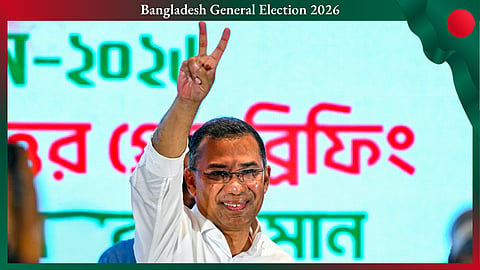

As Tarique Rahman prepares to assume office following the Bangladesh Nationalist Party’s (BNP) emphatic victory in Bangladesh’s general election, the result is widely interpreted as a mandate for centrist continuity after years of turbulence. The polls were the first genuinely competitive national election in over a decade. After three consecutive, widely disputed elections under the former prime minister Sheikh Hasina, the interim administration led by the Nobel laureate Muhammad Yunus restored a measure of electoral credibility. Voters responded with clarity.

Of the 299 seats contested, the BNP and its centre-right allies secured 212, with the BNP alone winning 209 – an overwhelming parliamentary majority, large enough to amend the constitution without opposition support as the majority of voters also voted “Yes” on a referendum for reform. Such dominance carries risks of majoritarian overreach. Yet the electorate’s choice suggests a preference for institutional stability over religious conservatism or the untested idealism of the 2024 “Gen Z” revolutionaries.

Mahfuz Anam, the editor of the Daily Star, described the outcome to me as an “extremely wise verdict.” By his assessment, voters signalled pride in their faith but rejected the idea of religion dictating state affairs. The mandate, he argued, reaffirmed Bangladesh’s long-standing instinct for centrist recalibration when credible alternatives are available.

Historical precedent supports that reading. Elections held under non-partisan caretaker administrations in 1991, 1996, 2001 and 2008 all reflected the electorate’s capacity to reset politics decisively. Voters rejected incumbents in each of those elections. In 1996, the ruling BNP, then led by Rahman’s mother, Khaleda Zia, lost to Hasina’s Awami League. In 2001, Zia returned to power, unseating Hasina. The pattern of anti-incumbency repeated in 2008. However, after securing a brute majority that year, Hasina scrapped the caretaker government provision from the constitution despite strong objections from the BNP, which then boycotted the 2014 polls. With that annulment, the framework for broadly accepted free and fair elections effectively collapsed. The 12 February election has rebooted the electorate-driven mandate for Bangladesh’s governance.