One monk’s lonely battle against Sinhala-Buddhist extremism in Sri Lanka

“ALMOST EVERYONE in this society is wounded,” Galkande Dhammananda said. “Reconciliation will take time.”

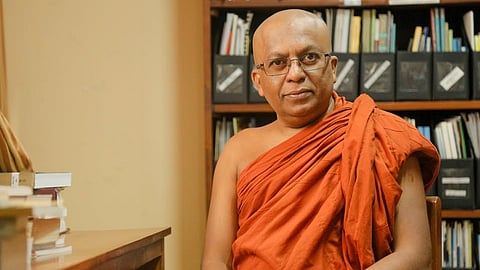

Dhammananda wears the flowing saffron robes characteristic of Buddhist monks in Sri Lanka, with his head shaven as per tradition. He has kind eyes framed by large, black-rimmed glasses. His face is smooth and unlined, almost ageless, with just a few worry lines on his forehead.

The most striking thing about him is his voice. It has a singsong quality yet somehow maintains a firm authority, despite how soft-spoken he is. Every word comes across as deliberate and measured. He does not seem the type to make an offhand joke or speak without thinking. In our conversations, it was clear that he is quite conscious of how his words may be perceived.

A Buddhist monk talking about post-war reconciliation is not a common thing in Sri Lanka, where monks have increasingly become synonymous with Sinhala-Buddhist nationalism and anti-minority rhetoric. Dhammananda is a rare exception – and perhaps the most prominent one – to this pattern.

The Aragalaya, the protest movement in 2022 that saw President Gotabaya Rajapaksa ousted from power amid Sri Lanka’s massive financial crisis, propelled Dhammananda into the public eye – especially after he appeared on a talk show on the news channel Ada Derana and at an event held by protesters to commemorate the victims of the 2019 Easter bombings.

Before we met, I watched one of Dhammananda’s talks on YouTube, delivered to the Buddhist Society of Victoria, in Melbourne, where he talked about his early calling. “When I saw monks, I found they are so calm,” he says in the video. “Particularly the monk who came to teach in my school, he was a very calm person. And I wanted to be one of them.”

On his way to or from school, Dhammananda would get down from his bicycle and converse with this monk every time he spotted him walking to a nearby monastery. At 13 years old, Dhammananda finally managed to convince his parents to let him join the order.

Watching Dhammananda’s videos, I was struck by how different he was to other Sri Lankan monks. As a Tamil woman, part of the country’s persecuted Tamil minority, I have often felt nervous interacting with members of the Buddhist clergy, especially as monks have become deeply entwined with the politics of Sinhala majoritarianism. But that strain of hate and rage seemed completely absent in Dhammananda.