In sickness and in health

(This article is part of our special series Unmasking Southasia: The pandemic issue. You can read the editorial note to the series here.)

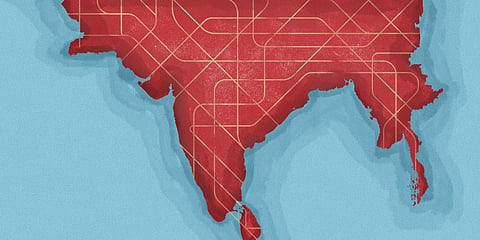

In many ways, the call for the regional revival of the South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation (SAARC) to respond to the COVID-19 pandemic in early 2020 was designed to fail. After all, the geopolitical red tape that followed the creation of the COVID-19 Emergency Fund played to a predictable pattern of gridlocked regionalism, with India and Pakistan at loggerheads about how the funding was to be disbursed. Plagued by chronic trust deficit, weak institutionalisation and stasis, Southasia once again finds itself between a rock and a hard place. This failure raises fundamental questions about how Southasia chooses to engage with questions of benefit sharing, trade-offs and the allocation of risks and burdens within the neighbourhood. But the current moment also marks an inflection point. While the regional project has never appeared more dysfunctional, its raison d'être has never been stronger. And interesting new examples of cross-border collaboration in the fields of public health and disease control offer potential pathways for Southasia to repurpose its regional project in imaginative ways.

Admittedly, a regional project that is already in crisis mode is ill-equipped to deal with the challenge of better regional cooperation. It is perhaps telling that SAARC tends to make news for cancelled summits, with heads of states having met only 18 times since 1985. This has resulted in a crippling policy vacuum that is there as much by default as by design. The top-down formal model that characterises SAARC has held it back from fulfilling its regional mandate. The caricatured image of the region as the least integrated in the world is not without basis. As per a 2018 study by the World Bank, intra-regional trade in Southasia remains at an abysmal 5 percent of the region's total trade. It has also not helped that the bulk of the trade is heavily skewed in India's favour. For instance, according to data released by Nepal's Department of Customs in early 2020, Nepal's trade deficit with India constitutes 60 percent of its overall deficit. Economist Mustafizur Rahman draws attention to the growing concern within Bangladesh about its rising trade deficit with India, which stood at USD 7.35 billion in 2019, with imports from India amounting to USD 8.60 billion, whereas its exports remain at a modest USD 1.25 billion.