Some incidents related to what she saw at the Mona Lisa Apartments

His name is Chandu. His father was Dewa. He discovers his mother's name when he is fourteen. He reads 'Sukki' in the death registry kept at the tehsildar's office. He's grown up without knowing his siblings' names, or even how many of them there were. The aunt in whose home he has sheltered says, "Never mind." But he waits many hours for the clerk to return with the necessary form so he can add to the registry the names his aunt gives him – 'Bidde', 'Kosa', 'Podiya', and the youngest, too young to be named, who the aunt remembers vaguely was simply called 'Bachchi'.

He is leaving the village for the first time. It is time for the one daily bus to depart, and the clerk still has not returned with the form. Chandu can no longer wait for the clerk. He boards the bus. He sits with his elbow propped on the sill and his face set in either anger or sorrow, the aunt cannot tell. Too late, she realises it is fear. She reaches, up on her toes, to touch him. And when the bus spits smoke, she takes two steps forward with it and cannot think of what to say to reassure him.

***

His aunt is the old woman who prays. She prays for him.

His aunt it is, who finds me for him. By that time he is working in a hotel in the city. He wants someone from the city for his wife. And educated, he says. And just like that I am no longer a girl with a red ribbon wound in her hair. His aunt comes to the city to live with us. We become three: Chandu, his wife, his aunt. She tells me I am nearly a daughter to her. She does not tell me what she knows: the reason why she prays, even in the days when we are three and the men have not come for him.

You can close your eyes and say to yourself 'watermelon' or 'football.' They are both round things that can be burst. If you cannot picture them bursting, think instead of them being sliced open.

***

Chandu splashes water on the floor. The water does not puddle there, it spreads over the floor, travelling in long spokes, radiating from some lost centre. He motions his wife to observe.

"What do you see?"

"You spilled water."

"Yes, but what is the water doing?"

"The water is flowing."

"Why does it flow?"

"Because the floor slopes, see?"

"No, the floor may slope, but that is not why water spilled to the floor flows."

"Why then?"

"It seeks its level. A stone floor might first have to be worn through, but water, and anger, both seek their level."

His wife is not impressed. Not even when he repeats the performance for each of their children in turn. Seven and a half years to give birth to three children, whom he teaches by spilling water on the floor.

She asks him what he meant when he asked for an educated wife. He speaks loftily of women who have their own story. She is amused. She has listened to him tell his father's story and his father's father's story. What, she asks, happened to his mother's story?

Chandu comes home with stitches crawling across his forehead.

Men who go to or come from the airport late at night or early in the morning are drunker than men at any other hour. The hotel is by the airport. It exists to cater to these men. The waiters are quick to step away from the tables, back as far as the far wall that they press their backs against. The men ask for more drink and curse the poor service that is huddled far away from them, back where the room is dark.

One man takes foil, and a paper that he rolls like a cigarette. They take turns, the three of them, cooking smack on more foil that they cut into shape with their cutlery knives. Later, foil lies crumpled on the table.

He tells his wife the details of what he saw. Of how the drug bubbled on this pan so thin.

"Like daal at home?"

"No, quicker, like the tadka. You have to pour it before it burns."

"Pour it?"

"Well, suck it in through the first thing they made – the pipe."

"I thought you said you were too far to see anything?"

She loses interest: he is making it up as he speaks. She hurries to ask him what and where and why the stitches. He tells her again about foil that lies crumpled on the table. A man, one of the three, lies crumpled on the floor. Another begins the slide from his seat to the floor. Chandu, seated on the rough concrete floor of their home, has trouble sliding his bottom along it to demonstrate.

"See, the seat is smooth, like leather, but plastic. I am the only one who approaches when the men shout."

She can picture it. The one who is sliding to join the one on the floor leaves a wet streak on the seat as he drags the rag of himself to his knees.

"They are shouting, and though I come fast one man throws the ashtray. It is glass but it hits me like a brick."

She touches the curving bite of thread. From his right ear it chews its way across his right eyelid and halts only on reaching the gristly meat of his brow.

The men are angry. They push past Chandu to the piano player, shout at him to play, push him from his seat, and take away the piano-seat. "Sisterfucker. Won't play when he is told to. Now there's no way for him to play, is there?"

***

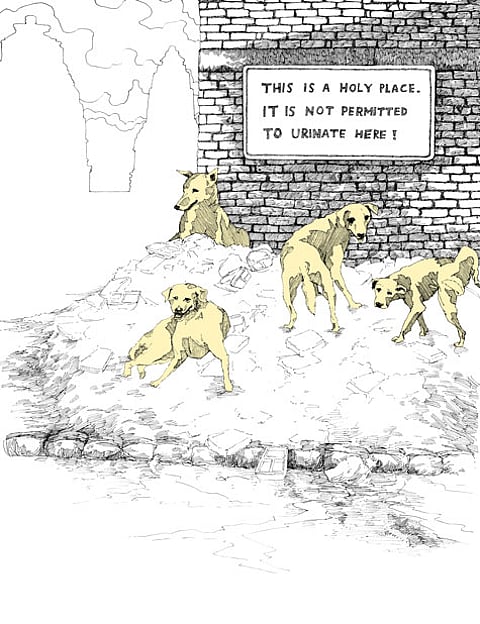

His aunt is still praying. Her lips move without stopping. She holds a Styrofoam plate; it is tilted away from her; the food heaped into its compartments is in danger of spilling out. Plates lie tossed away everywhere along the footpath and in the street. Some plates have been tossed onto the rubbish pile. Above the pile, the sign on the wall says, "This Is A Holy Place. It Is Not Permitted To Urinate Here." His aunt staggers toward the rubbish heap. Yellow dogs follow her. Some other yellow dogs chase plates, which skitter and slide from their tongues. His aunt seats herself some distance from the vigour of their begging tails.

But this is comical. How will his aunt pray and also eat?

She has not stopped praying since the evening before. The dogs watch to see what she will do. I, Chandu's wife, sent her to the temple for the free meal. I watch from my doorway across the street.

Standing in the doorway and watching his aunt not eat, I am conscious of myself, my skin that rides the rise of my breasts, swelling to nowhere, nothing, never. He will not return. I can still breathe.

***

The clerk at the tehsildar's office – not the one who failed to show up before the bus taking Chandu to the city left, but the clerk before him, actually the father of the tardy clerk – remembers the baby who survived the drought of 1967 and came crawling to extend a hand and receive rice ladled out from a pail. This clerk is retired, but comes out of retirement when the men come with their sticks and questions. He is a man who remembers – "Chandu". He gives the name easily. He adds, "Chandu comes and goes from the city."

In this story, an old woman prays. She prays right through to the end of the story.

Do you think you might be able, suddenly, to run fast enough to outrun a lion? What if it were chasing you? Do you think you might possess a reserve of strength that could translate into speed?