The dark white shroud

In the winter of 2002-03, a protracted fog hugged the ground of the Indus and Ganga plains in the north and east of the Subcontinent for approximately 45 days. The resultant seet lahar (translated as 'cold wave') of December and January condemned 500 million people, living in a swathe of territory from Rawalpindi to Rangpur, to a sun-starved and frigid existence.

The fog disrupted life beyond just upsetting local airline schedules and delaying trains. In this, one of the most fertile belts of the world – the tropical and semi-tropical northern half of South Asia – lives a large section of global humanity, mostly in poverty. And it was exposed – under-clothed, undernourished – in the millions, to temperatures in the low single digits. The fog and the accompanying cold of the winter just passed struck a bitter blow.

The effects of this winter fog are compounded every year when its growing incidence coincides with the growing numbers of those it shrouds. Yet, as Himal's investigation over the last two months has confirmed, the Indus-Ganga fog is a grossly understudied meteorological phenomenon. This shortcoming is evident when one begins to examine available literature. Meteorological data confirm anecdotal information that the duration and thickness of fog in the Indus-Ganga maidaan has been on the rise over the last half century, yet there is a singular lack of academic concern over its socio-economic impact, and not enough scientific interest in investigating comprehensively the factors behind this increase. While the changing air quality, which appears to have a significant impact, and the inversion layer that now persists for long periods of time preserving cold air at the surface, have received some attention, the rise in ambient moisture – more significant for the plains than in deltaic Bangladesh – as possibly a major cause has been neglected.

The familiar term 'cold wave' does us great disservice in this by implying that the cold comes from elsewhere. Even experienced meteorologists will fob off enquiries by invoking the 'northwesterlies' to explain away the cold as something nothing can be done about. True, the northwesterlies that blow over the land in the winter are cold moist winds that come from elsewhere (as all winds must), but they have always been coming down from that direction and therefore are a constant factor. In fact, the cause for the cold, in the sedentary fog that sits on the Indus and Ganga plains keeping the sun from warming the land and its people, may just be homegrown.

Engineering in this region, from Pakistan's Indus basin to the Nepal tarai, has interfered substantially in the last 50 years with the natural hydrological cycle of the plains. The result is that there is a lot of unseasonable water on the surface in the winter due to irrigation canals, the pumping of groundwater and the building of embankments and other structures which cause waterlogging. The impact on the weather of this ecological modification has gone entirely neglected by the Subcontinent's scientific community.

Finally, there is a distinct lack of caring when it comes to the impact the fog has on those living in abject poverty here, who number in the hundreds of millions. Living in a region that is warm or hot most of the time, even under normal circumstances the poor do not have the clothing, the diet, the shelter or the services to cope well with the cold. Given that historically the seet lahar lasted no more than a few days, it was possible to overcome the brief misery. But, with the number of foggy days extending up to a month or more now, misery levels have risen, and continue to rise. An index for this misery has not been proposed, let alone configured – not by physical scientists, nor by social scientists. While the media reports separately on the fog and the cold, there is no attempt to link the two and analyse the inescapable trend.

The fog has caught the metropolitan media's attention mainly because of poor visibility – flights and trains are often cancelled or delayed. Occasionally, when the numbers are sufficiently impressive, there is disconcerting news of so many "cold wave deaths" and the plight of the urban homeless. But the loss to the economy has not yet been calculated, the destruction of winter crops, the standstill in the brick-making industry, the slump for builders and masons, the impact on dhobis across the land whose clotheslines remain soggy in the absence of sunshine, and a hundred other professions and industries that are affected by the fog suffer without registering on the radar screen.

Sociologists have not thought it necessary to discover the number of people affected by the extended presence of the winter fog, and no public health expert has considered its impact on them in terms of problems from the exposure, particularly affecting pulmonary resistance. No observer or analyst has considered the fact that the duration of the seet lahar (though getting longer, yet short when compared to the hot months) makes it unviable for the poor and very poor to even aspire to add a winter wardrobe, or to buy quilts, or build a heat-conserving space in which to live. In the Indus and Ganga plains, which register among the lowest on human development indices anywhere in the planet, it just does not do to say, "Let them wear sweaters", for people have only ever had to plan for thin cottons.

Flying blind

In his novel Blindness, Portuguese novelist José Saramago describes the progressive blindness of an entire city and the consequent breakdown of social order. Social order may not be under threat in this case, at least not yet, but the Subcontinental fog in its engulfing whiteness, and in the neglect of it at various levels of investigation draws a parallel to Saramago's tale. While the intuitive conclusion that the incidence of fog is on the rise finds numerical validation, most meteorologists still hide behind the "need to study data" before pronouncing a trend. Rather than concede to this insensitivity, Himal decided to extrapolate from its collated findings that the northern half of South Asia is indeed a foggier and more miserable place now than it was even in the 1970s.

As per the definition used by the Indian Meteorology Department (IMD), fog is the condition in which horizontal visibility on the surface is less than 1000 metres while relative humidity (RH) is above 75 percent. There is nothing new about the science of fog, and it still develops when there is the standard mix of atmospheric moisture, aerosols around which this moisture may condense, and appropriately low temperatures for the condensation to occur. The science of fog has not changed. What has is the increasing severity of the fog (and correspondingly the cold), in terms of both how long it lasts and how thick it is.

Weather data lie at the core of meteorology, and the best place to seek continuous data on the fog is the aerodrome, where meteorologists are more exercised than others about its incidence. Reduced visibility disrupts flights and inconveniences the privileged of an underprivileged Subcontinent.

Data from Safdarjang, now an under-used airstrip at the heart of New Delhi, reveal that of the last six Decembers, four have had over 20 foggy days. Compare this to the average of 6.2 days of fog for the month of December between 1951 and 1980. The average for January at Safdarjang was 6.8 foggy days. However, only in one year between 1996 and 2003 did New Delhi have less than 20 foggy days in January. This dramatic rise in foggy days in Delhi is repeated again and again in airport weather stations across the north Indian plains, whereas data from the south or from the Himalayan region do not show the trend.

A study was published in October 2001 on visibility at 25 Indian airports across the country, conducted by a team which included US De, former assistant director-general at the IMD. It shows that at 21 northern stations, the number of days with visibility of less than 2000 metres (the benchmark commonly used as the 'runway visual range') in the winter months (December-February) is on the rise. Tracking trends through the 1970s, 1980s and 1990s, the graphs for Allahabad, Amritsar, Benaras, Delhi, Lucknow and Patna are particularly steep.

In Amritsar, the number of poor visibility days has shot up from two out of 90 in the 1970s to 72 out of 90 days in the 1990s. Benaras registered an increase from nine foggy days to 72, Lucknow and Allahabad, from nine to 63, and Patna from 12 to around 75. The meteorologists, writing in the journal Mausam, say that "in the north Indian stations viz., Amritsar, New Delhi, Varanasi, Patna, Lucknow and Allahabad… the visibility deteriorated significantly with poor visibility days increasing to 70 to 80 percent in the winter season".

Learning from recent experience that the fog has begun playing havoc with domestic and international flights, the airport at Palam in Delhi upgraded its landing instrumentation system this year to enable aircraft arrivals at even 500 metres runway visual range. But the fog beat the technology with visibility keeping well below that mark except for a small window during the day when the rush to clear flights often overwhelmed the system.

Irate passengers make for chaos at airports and may give airlines a bad name, but they are after all, at worst, only inconvenienced. The fog and the cold made obvious yet again the startling income inequality in the fertile plains of the Subcontinent. On the one extreme, in Lahore and Delhi, the two major international airports in the affected area, the hotel business picked up with five-star establishments gaining substantively from disrupted air traffic in the first three weeks of January.

At the other extreme, in Bihar, where the government distributed blankets in the last week of January, almost four weeks into the fog, only those who could prove below poverty line (BPL) status could take refuge in state largesse. Never mind that BPL computation is so flawed that it is not a realistic reckoning of poverty at all, the Bihar government linked blanket distribution to BPL schemes that require the applicant to furnish an address. As a result, not only were the not-poor-enough bereft of state protection but the too-poor were left at the mercy of the weather as well.

Meanwhile, it was reported that room heaters, blankets and hosiery saw brisk sales this winter.

Nepal tarai

The Indian airport data provide convincing proof to support accounts that the Ganga plains have seen a dramatic increase in the incidence of fog and extended cold periods during December and January. The same seems to hold true, across the western frontier, in Pakistan, whose national meteorological department reported that, in January 2003, "The mean daily bright sunshine duration remained below normal all over the country due to persistent fog". Specifically, "thick fog persisted over the agricultural plains of Punjab and NWFP [North West Frontier Province]".

The conditions in Nepal's 800 km stretch of the southern plains are mirrored in the adjacent areas of Uttar Pradesh (UP), Bihar and north Bengal. In its preliminary weather summary for January 2003, the Department of Hydrology and Meteorology in Kathmandu dwells at length on the abnormally severe fog in the tarai. This year the tarai region reported "dense foggy weather resulting in severe cold condition for the long period from the last week of December 2002 till 24 January 2003… The sun was completely obstructed by the dense fog, preventing the sun's ray from reaching the ground".

The department's figures for December and January over the last two decades suggest that the tarai, from Dhangadi in the far west near Pilibhit in India to Biratnagar in the east, close to Siliguri, is becoming progressively colder during the day but rarely registers negative variations from the normal at night. (Cold days and warm nights, as the meteorologist will confirm, usually indicate fog or cloudiness.) In January 1983, Dhangadi's mean maximum was 20.2 degrees C, -1.5 from normal. In 1993, the variation was -2.6 degrees C; in 1998, -4.1 degrees C from normal; and finally this year, -6.1 below normal.

Right across the stretch of the tarai, Nepalgunj, Bhairahawa, Simara and Biratnagar are on a similar trajectory as Dhangadi while, interestingly, Kathmandu valley and other hill towns seem headed the other way. There are ample narrative accounts in the tarai about the increased incidence of the fog. To begin with, conditions are such now that the plains folks, incongruously, have started heading up the hills to find sunshine and warmth. Since the ground-hugging fog does not extend beyond a couple of hundred feet, sunshine is often less than an hour's drive away. Says an anthropologist who grew up in the tarai town of Butwal, "I never remember fog in Butwal, but now to escape it and the cold, people go up to Palpa for warmth". Tulsi Basnet, a Butwal businessman, closed his shop and undertook the hour and a half's bus ride to Palpa to reach the sun's healing warmth. He says, "We heard it was sunny in the hills; we had to go there to give my father some relief from his asthma".

For at least the period of the seet lahar, the remote Himalayan districts of Nepal are actually warmer than places in the plains. Nepalganj is known to schoolchildren through their primers as the hottest town in Nepal. But these are abnormal times, and this year, for days on end fog-stricken Nepalganj was colder than the remote mountain district headquarters of Jumla directly to the north. At 2340 m elevation, Jumla had bright sunshine while in Nepalganj underclad ricksa-pullers shivered in the fog. On 19 January, for instance, Jumla recorded a daytime high of 21.3 degrees C, while Nepalganj had a maximum of 10.4. Two days earlier, Kanpur in UP, among the hottest places in the region in summer, recorded an "unverified" minimum of -0.6 on a night when yet again Srinagar, up in the Kashmir valley, was warmer.

Says one Kathmandu-based editor, "We used to hear of people dying of the loohoo, or heat wave in the tarai. Now more people are suffering and dying in the winter, and in a shorter period of time. And, it is the same people affected in both summer and winter, without air conditioning and without heating".

Globally, the weather may have changed incrementally over the past few decades, but climatic factors such as prevailing winds have remained relatively constant over the period. Given that, the moisture-bearing low-pressure northwesterly winds are ascribed more than their fair share of the blame, as they cannot be the explanation for the steady rise in winter relative humidity and Indus-Ganga fog over the last few decades. Instead, three key variables in the increasing fog are moisture, pollution and temperature inversion. The inversion layer, when normal atmospheric temperature 'inverts' so that it is coldest near the surface getting warmer with altitude, results in a cap where cold (in this case, polluted, foggy) air is trapped at the bottom. In the Indus-Ganga winter, a strong inversion layer forms at a low-level, which increases the longevity of the fog. The other two factors relate to human intervention in the Indus-Ganga belt: greater air pollution in the lower atmosphere, and the increased presence of water and moisture on the surface during the winter months.

Command areas

There is now an unprecedented amount of surface moisture in the Indus-Ganga belt in the cold months, when historically the land would have been dry other than during the brief spells of winter rain. This appreciable increase in the presence of surface water is explained by the three following factors.

First: the building of a network of canals all over the plains over the last half-century, particularly in India and Pakistan where, post-independence, irrigation gained credence as the panacea for illnesses that ranged from rural poverty to agricultural production shortfall to the 'burden of backwardness'. So, from just a few hundred kilometres in 1950, there is now a network of thousands of kilometres of canals carrying water year-round to the 'command areas' that cover the length and breadth of the Pakistani and Indian Punjab, Haryana, UP and Bihar. Today, in the Indian Punjab, 1,527,000 hectares are under irrigation. Next door, the Indus Basin Irrigation System, the world's largest irrigation network comprising 45 main canals, diverts almost 75 percent of the average annual river flow into the Indus basin, irrigating 17 million hectares of contiguous land. In UP, total canal length grew by 3100 kilometres in the 14 years between 1972 and 1986 alone.

Second: the revolution in the exploitation of groundwater for irrigation, powered by diesel pumps and electricity subsidies, now brings to the surface water which stayed underground before this. Today, deep boring brings up sweet water to irrigate vast swathes of land, bringing unprecedented prosperity to some areas, but helping in the creation of fog conditions, which in the end adversely affect the very crops being irrigated.

Third and finally: the building of concrete embankments to control the waters of the Indus and the Ganga, which has been a 'growth industry' over the last five decades, takes its toll. Pushed by the perceived need to protect the people from floods, the embankment (tatbandh)-construction has become a populist measure used by political parties, with the active collusion of private contractors, to show their concern for the people. Over time, the activity has generated a momentum of its own, and the cumulative length of rivers roped in behind embankments has increased from almost nil in the early decades of the 1900s to thousands of kilometres today. In Bihar, where the tatbandh mafia is particularly influential, the total length of embankments grew from 154 km in 1954 to 3500 km in 1997.

The effect of both canals and the embankments is the same, ie they increase the moisture content of the soil or allow bodies of water to exist outside of the natural watercourses. Canals, by definition, divert water to areas where there is naturally none. And embankments, while they block floodwaters in the monsoon, play a significant role in ensuring that water does not properly runoff into the rivers. Year-round, as a result, there are large pools that do not drain out. Flawed engineering in both cases ensures seepages that result in waterlogged fields. Thus, an estimated 182,000 hectares of 'protected land' are waterlogged outside the eastern Kosi embankment, and another 94,000 hectares on the western side, apart from the 34,400 hectares waterlogged above the contour line.

The other variable, pollutants, plays an undeniably active part in the intensification of the fog. Particulate matter in the air act as nuclei for water vapour to condense on, and over the years, the increased activity of a rapidly growing population in transport, agriculture and other sectors has dispelled into the air a variety of pollutants. The effects of winter cropping, vehicular emissions, the output of tens of thousands of brick kilns and other more modern smokestack industries are only now being studied in some scientific depth. The effects of the greater availability of surface moisture from irrigation and embankments, meanwhile, have yet to ignite even a spark of interest in the scientific community.

Seet lahar

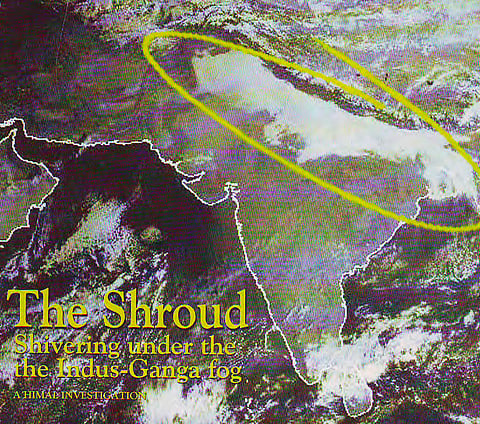

The most graphic visualisation of the fog is to be had from satellite imagery. The image on the magazine's cover, for example, captured by the geostationary satellite Indian Ocean Data Coverage (IODC), shows vividly just what the north South Asian fog is about. Hour after hour, day after day, an enormous white sheet wraps itself over the super-hydrated plains, staying stubbornly in place, only its edges fraying or consolidating, while clouds (which one can differentiate from the fog by a thin line of telltale shadow) and jet streams move over Asia and the surrounding oceans.

The term 'seet lahar' captures most evocatively the condition of the Subcontinental cold wave. Seet, which may be employed to convey both 'cold' and 'dew', however loses some of its dampness in English, breaking the connection between water and the winter for the influential English-educated in the Subcontinent. Indeed, because the term is translated into 'cold wave', the impression is of a chill blowing in from some distant trans-Himalayan region. Whereas the reality is that the long periods of cold of the last few years are linked to the increasingly longer periods of fog, which is actually predicated on the absence of winds any stronger than eight km per hour. Of course, not all cold days have to be foggy. 'Western disturbances' are known to bring gusty winds and rain, which bring the temperature down. But these conditions prevail over a period that is accurately described as a 'cold snap' – intense but brief. The protracted cold wave periods, in contrast, are about days on end of fog-induced misery.

Turning to the science of the fog, consider this. For two samples of air at temperature T, the one with more water molecules will have a higher dew point, which is temperature at which water vapour condenses to form water droplets or fog. So, even 'normal' semi-tropical temperatures (such as in the Ganga plain) that do not dip very low are conducive to fog formation because of the high atmospheric water vapour content. Then, because water droplets or fog are an even more effective absorber of radiation than water vapour, not only does the fog prevent the sun's rays from reaching the huddled masses of the Indus-Ganga plains, but it actually sucks up what heat is available in the atmosphere and soil. However, perhaps by force of habit, meteorologists continue to attribute winter humidity to the moisture-bearing northwesterlies, failing to explain the recorded rise in relative humidity at northern stations or connect it with the rising incidence of the fog.

The hundreds of millions of penurious or near-penurious, who are the worst hit, may know intuitively that the fog's incidence is on the rise but as with every water-related contention, they will yet again not determine what must be done about it. Instead, it is the influential pockets of urban South Asia, where those with access to woollens, electrically wired homes and heated vehicles live, only briefly exposed to the cold between the house and the car, that will persuade studies, legislation, even activist judges to consider the problem. They have heard that the fog has to do with the unacceptably high air pollution, and consequently, air pollution now occupies inordinate space in the 'national' consciousness. So, evening news features include minutiae on daily decimal variations of CO, NOx and SO2 emissions, and the study and resultant activism with regard to air pollution in New Delhi inspires even the lofty Supreme Court of India to plunge its gavel into the matter.

The apex court's exertions seem to have borne fruit with pollution levels having palpably altered in Delhi. But this has not had the expected corresponding effect on the fog, which continues to intensify even though pollution levels have fallen. This seemingly incongruous eventuality has prompted perhaps the only investigative study of the fog in India where, expectedly, the link being probed is the pollution-fog one (see box).

Having taken care of urban air pollution, the court has since shifted its attention outside the city, to direct the Indian government on a grand multi-crore "garland canal" scheme that will connect parched areas of India to 'water-surplus' areas. The effects of this are inconceivable in their entirety, not least because the matrix of the climate has not been comprehensively mapped yet. The immediate consequences are apparent though – massive rural dislocation, and the magnification of the already well-documented problems with canal irrigation.

Not among these well-documented problems however, is the one of fog. Indeed, there has been considerable study and activism related to other aspects of the hydrological cycle in the Indus-Ganga region. Organisations as diverse in approach and focus as the research and public information oriented Centre for Science and Environment in New Delhi and the Bihar-based activist river movement known as the Barh Mukti Abhiyan have fought political, bureaucratic and engineering obtuseness related to flood-control and waterlogging for years. However, even they have not yet made the link between canals, embankments, groundwater exploitation, the fog, and the misery it brings.

While this investigation by Himal suggests a causal link between faulty water engineering and the fog, the hypothesis needs to be scientifically investigated. A serious study must be followed by a sensitisation of those who matter, and (to the extent possible) mitigation measures to reduce the bitterness of the winter for those inadequately clothed or housed.

The exceptional situation of the Indus and Ganga plains is that for most of the year it is a hot and humid home for its overwhelmingly large population, where the poor expectedly have not evolved mechanisms to cope with cold. In the cold higher latitudes of the Chinese heartland, which also has a large population of poor, and where too the fog may be intensifying, people are prepared by historical experience to deal with the harshness of winter. In Sub-Saharan Africa, where a large number of the world's extremely poor live, it will never be cold or foggy. In the Indus and Ganga plains, however, the relative brevity of the bitter fog and cold renders unviable the building of new structures and the procuring of warm clothing – moreover, many would not even have the place to store such new clothes. So north South Asia, uniquely, is a site where people in the millions suffer from not having insulation through clothing or construction, a deprivation that is as primal as not having food.

Vegetable crop

Whether in terms of construction techniques, purchasing power or agricultural practice, the sub-tropical north of the Subcontinent is fundamentally unequipped to deal with either the fog or the cold. Winter is still remembered as the season of relief between harsh summers and the long monsoons. Instead, it has become a dank cold season with endless days of physical and fiscal distress. For those with material means, it is distress over the crop or business, or medical bills and delayed travelling. And for those who have nothing, such as the millions of urban homeless, it has become the season for worrying about survival. With the sun's rays not penetrating the thick fog, hundreds of millions of people in the Indus-Ganga plains have just spent a season immiserated.

While the loss of human lives to the cold has been computed (at 1500 for this winter), a material cost evaluation exercise has not been carried out at the governmental level in Bangladesh, India, Nepal or Pakistan. That verified figures are not forthcoming on this issue is not, for once, due to official unwillingness to share data but rather to a complete lack of imagination. Dr RP Singh, head of the Department of Agricultural Economics at the Indian Agriculture Research Institute (IARI), concedes that putting a figure to the agricultural losses would be "socially relevant". And yet, a researcher at the institute shrugs off the suggestion, saying such an exercise "would not be economically viable in a developing country such as India". It is through cracks like these, in the disconnect between politicians and scientists and the 'constituency', that the common person falls.

Take the case of Prakash Yadav, who is chief whip at a taxi stand in DLF Gurgaon, a suburban Delhi locality. Gurgaon straddles Delhi's urban conglomeration and Haryana state, and many like Yadav travel the short distance from their fields in the latter to the bustling urban economy. Like so many others he knows, Yadav too has suffered the ills of the last few winters. While almost 40 percent of his mustard crop was laid waste by white rust, a fog-related disease, he calculated a 50 percent dip in his earnings from the taxi service for December and January.

Even if the scientists and administrators have not yet made the connection, the peasants and small farmers know well that the intensity of the winter fog is on the rise. In the Subcontinental belt under consideration, the major winter crops are wheat, mustard, potato and pulses. In India, owing to government policy fashioned in response to food grain surplus, vegetable cropping has for some years now been replacing wheat cultivation. The policy calculation obviously factored in import, export, storage costs, supply and demand, but it neglected, not atypically, to look at the data on the ground. Wheat is a hardy crop as compared to the 'short-duration young crops' of winter vegetables that farmers have been encouraged to adopt, which cannot withstand sustained exposure of even four-five hours to above-80 percent relative humidity in combination with temperatures as low as seven-12 degrees C in the crop canopy. Relative humidity above 80 percent promotes bacterial development, and this winter, when RH stayed as high as 90-100 percent for as long as 10 hours a day, the conditions were devastating. White rust and alternaria blight struck the mustard this winter, and blight also affected other common winter crops including potatoes, tomatoes and brinjals.

Dr NVK Chakravarty, principal agricultural meteorologist at IARI, explains that the late-sown varieties of the vegetables are particularly vulnerable to the cold and fog. They are late sown because timetable for multi-cropping, an irrigation-enabled practice, is not quite synchronised yet. Thus, the plants are still in the early stages of development when the fog develops its intensity, and a high level of humidity promotes bacterial growth. Additionally, the fog also affects photosensitive growth activity in the plant, and low temperatures retard its development.

The narrative of human ambition vis-à-vis nature that frames the story of the fog is sublimated in the potato. The potato is not indigenous to the Subcontinent, but almost all major viral, fungal and bacterial diseases that it is vulnerable to are endemic here. An input-intensive crop requiring fertilisers, irrigation and expensive hybrid seeds that will enable it to fit an alien agronomic pattern as a short-duration crop, the potato never caught on in the Indus-Ganga plains till rapid canal proliferation post-independence, and state-inducements, made it possible. This winter, potato farmers from NWFP to north Bengal suffered crushing losses possibly because of the same irrigation network that enabled this unnatural cultivation in the first place.

This winter was perhaps the worst for potato and mustard, but numbers are hard to come by. In January, IARI estimates for Punjab's losses (which contributes almost five percent of the national yield) varied wildly between 15 percent and 40 percent. In West Bengal, where 32,000 hectares are under potato cultivation, farmers were told to use pesticides when it became apparent that the fog would linger long enough to ruin the crop. Says Dr S Mishra, an agricultural meteorologist with the West Bengal government, "There is definitely an increased incidence and duration of fog during the winter months in this region. This is based on observation; we have not done any study on the phenomenon".

The absence of econometric application to fog by those whose job it is to do such study is glaring. An aggregation that takes into account aviation, railways and road transport, commerce, agriculture and industry, vehicular accidents, costs of delays, public health expenses, among others, has not been done and is not on the cards. Only if such an investigation is undertaken will ironies such as the plight of the potato farmers of the plains find a narrative framework. As things stand now, Prakash Yadav's woes continue to be blamed vacuously on the 'cold wave and unusual fog', while meteorologists debate endlessly whether the conditions are a regional manifestation of global climatic changes and the establishment as a whole prefers not to involve itself too deeply in this complicated and potentially controversial subject.

Cold threshold

Over the last few decades, the ground fog has grown from localised patches into an enormous blanket, as satellite imagery shows. While images from the early- and mid-morning show it covering a stretch from the Northeast to Pakistan, more usually, the concentration tends to be in between these two extremes. In that region where dense fog has recurred year after year, growing towards its present spread and intensity, live at least 400 million people. Of these, as per calculations from the most conservative government estimates, the poorest of the poor, those who are denied the basic opportunities of life to procure even adequate nutrition, number no less than 150 million. An additional 200 million, while not maybe 'the poorest', is still too poor to afford a severe winter and would need substantial state assistance to weather it.

Among this aggregate 350 million who were most profoundly affected by the fog and cold of the recent winters are groups such as the kamaiyas of the Nepal tarai, a traditionally disadvantaged community of former bonded-labourers that has received little support from the state after being 'freed' by it. At least 46 kamaiyas, mostly infants and the elderly, died in ex-kamaiya camps this winter from pneumonia and upper respiratory tract diseases. These deaths were not caused by sheer cold – temperatures have to be much lower than those in the region to induce hypothermia – but were contributed to by the fog. The cold and damp of the fog simultaneously weakens natural defence mechanisms, especially pulmonary resistance, and since high relative humidity promotes the formation of acid aerosols, increases toxicity in the atmosphere.

Though the kamaiya system has been abolished, it will be a long time before the thousands who were yoked to it will be able to afford special provisions – of such basic winter items as blankets, woollens and closed shoes – for the foggy days of winter. Whether in UP or Bihar, in the Nepal tarai or the Duars of West Bengal, in Punjab or NWFP, the majority of the people do not have the wherewithal to materially bolster themselves for two extreme seasons, especially when the winter season is barely even a season – lasting in its unbearable intensity for all of a few weeks.

One is struck by the oddness of it all. The same steaming plains which once repelled the first Mughal, Babar, making him homesick for the cool climes of Kabul, this year, at 1500, were the site for three times as many deaths in the five weeks of foggy winter than in the four months of summer last year when 400-500 people succumbed to the heat. This year's experience will likely be a variant, a spike like was seen in 1997, a particularly severe instance, but still within a larger trend. The next winter will be judged against this one, and if not cold or foggy 'enough', which it will very likely not be, the season just passed will be remembered as an aberration. But, going by the data, the trend is a reality; only its causes may be open to discussion.

Someone do something

No doubt that climate is a complex rubric, and we are yet to figure out how exactly all the pieces fit. Perhaps it is really not even possible to conclusively answer questions of such proportions. But the Subcontinental fog, which may not even be caused by macroclimatic changes, should not be neglected because grander impossible questions might be attached. There is enough indication that the Indus-Ganga plains show a growing incidence of fog for it to warrant a scientific investigation from every possible angle, going beyond what this journalistic investigation has laid out. Probing the proximate link with pollution is clearly one. Another must be the rapid and relatively recent introduction of growth in surface moisture from groundwater extraction and the agglomeration of canals and embankments.

Regardless of whether the intensification of the Indus-Ganga fog has a causal relationship with the proliferation of canals, embankments and tube-wells, assuming it will recur at its current rate if not worse, a comprehensive loss calculation exercise must be undertaken. Only a quantified account of the gloom will enable the building of a model to try and reduce avoidable losses, and for streamlining costs which, as is the nature of losses, will mount if neglected. Also, to the extent that the fog can be minimised, such an analysis is indispensable for calculating whether the investment required yields a justifiably substantial drop in losses. Until figures can be ascribed to it, the fog will continue to be the shroud over the Indus-Ganga maidaan.

Even if the fog were not more prevalent now than before, it would have been time for sensitive scholars and administrators to consider the difficulties faced by the population due to it. Now that it looks as if the duration of the fog has risen dramatically, it is the duty of those in positions of responsibility, direct or indirect, to delve deeper into the phenomenon. It is simply not fair to say, as so many did to the reporter in the course of researching this article, "We do not know; no one has studied it".

Smoky days

The National Physical Laboratory (NPL) in Delhi, in partnership with the IMD and the Central Pollution Control Board, is currently perhaps the only organisation studying the Ganga fog. Still in its nascent stages, the two-year-old study has focused on the effect of air pollution on the formation of fog, and has found that the two are not as simply linked as first thought. The NPL says that the particular interactions of individual pollutants – hygroscopic emission gases such as NOx, SO2 and CO, greenhouse gases and the secondary pollutant, surface ozone – warrant special attention. The NPL study has discovered two things: that the concentration of aerosols influences the size and distribution of activated fog nuclei, affecting the fog's liquid content and visibility. And, that the activation of fog nuclei occurs at different levels of supersaturation for different aerosols. Working on the hypothesis that fog density, frequency and longevity must depend on aerosol properties, the NPL team is investigating the particular ways in which different pollutants influence fog.

Pollutants affect the development of fog because exposure to aqueous air promotes chemical growth resulting in the evolution of aerosols, which become the nuclei for water vapour to condense on. While the formation of fog is predicated on low wind speed, clear nights, high humidity (above 80 percent, but especially between 90 and 100 percent), appropriately low temperatures and the presence of pollutants, according to Dr MK Tiwari of the NPL's Department of Radio and Atmospheric Sciences, the strength (density and longevity) of the fog depends on the concentration of hygroscopic pollutants and the low-height temperature inversion layer.

In the Subcontinent, low-height inversion in particular fosters the longevity of the fog. Land being a better radiator of heat than air, after sundown, it and the air close to it cool expeditiously as compared to the air above, thus 'inverting' the normal state where air gets cooler with height. While, as the night wears on, the air at ground level cools to its dew point promoting fog formation, the cap formed by the inversion layer stifles wind movement, discourages cloud formation and keeps the pollutants, including water vapour, trapped. Temperature inversion should be strongest over those soil types that absorb, and subsequently release, heat most easily, ie sandy surfaces. But the truly arid regions in west South Asia are spared the phenomenon because of strong convection, typical of desert environments. In semi-tropical UP, Bihar and the Nepal tarai, where the inversion layer does not persist, there is enough moisture available from the irrigated surface and low-pressure northwesterlies, and temperature and pollution conditions are aggravated enough, for thick fog to linger for long periods into the day.