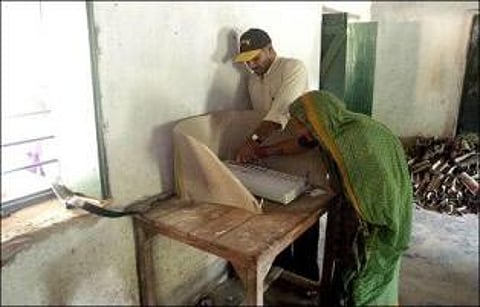

The ritual of the ballot

The story of democratic transition in Southasia is incomplete. Although all members of SAARC possess autonomous electoral-management institutions or election commissions, there have been notably few investigations into strategies used to enhance their independence. Such a lack of priority placed on the institution of the election commission has been detrimental for democracy in all the countries of Southasia. Historically, election commissions (ECs) have been viewed as representing the interests of the ruling political faction, and have been known to rubberstamp flawed elections. This has been a view confirmed by the 2002 general elections in Pakistan (where an executive order reconstituted the EC just prior to the election) and in the 2003 presidential elections in the Maldives (where President Maumoon Abdul Gayoom was re-elected to a sixth five-year term with 90 percent of the vote).

The story of democratic transition in Southasia is incomplete. Although all members of SAARC possess autonomous electoral-management institutions or election commissions, there have been notably few investigations into strategies used to enhance their independence. Such a lack of priority placed on the institution of the election commission has been detrimental for democracy in all the countries of Southasia. Historically, election commissions (ECs) have been viewed as representing the interests of the ruling political faction, and have been known to rubberstamp flawed elections. This has been a view confirmed by the 2002 general elections in Pakistan (where an executive order reconstituted the EC just prior to the election) and in the 2003 presidential elections in the Maldives (where President Maumoon Abdul Gayoom was re-elected to a sixth five-year term with 90 percent of the vote).