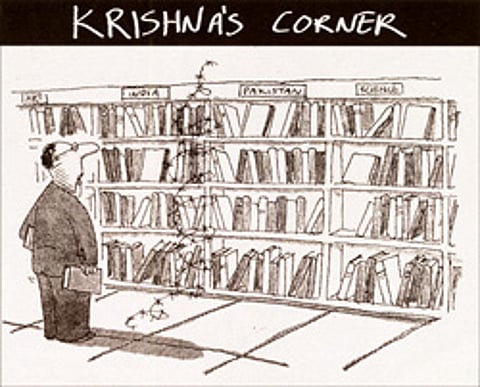

Two hands to clap

| Artwork: Vintage Himal, 1998 |

In his comparatively recent and strikingly honest book Rescuing the Future: Bequeathed misperceptions in international relations, India's former foreign secretary, Jagat Mehta, points out that no other mainland region of the world has such natural interdependence as what he calls "the sub-Himalayan sub-continent". So SAARC could be a particularly effective regional cooperation organisation; but it isn't. Whilst in Southeast Asia, Europe and North America, regional cooperation is the name of the economic game, in Southasia inter-regional trade and investment is a sorry story of missed opportunities. As for interregional communications essential for economic cooperation, they are almost nonexistent. There have been small improvements here and there. The Kashmir buses and the recently introduced train between Calcutta and Dhaka are two examples. But there are still no transit facilities for Indian goods and passengers across Bangladesh, and no passenger sea-links between India and Sri Lanka. Those air services between Southasian countries that do exist would be wholly inadequate for a region in which trade and tourism were flourishing.

So what is the reason for SAARC's inactivity? It is all too simple to blame Partition. While it does cast a long shadow over relations between India and Pakistan, the residual scars of Partition in Bangladesh should have been healed by India's support for its independence. Why should Partition affect India's relations with the other Southasian countries? When British India was being partitioned, Europe had barely begun to recover from the Second World War. Now, the European combatants are members of a union of states. There were histories of hostility among the Southeast Asian countries, which had to be overcome before the members of ASEAN trusted each other.

Geography is a far harder problem to overcome than history. India is much larger than any of its neighbours, and more powerful both in economic and military terms. Size and power breed fears of domination, and can all too easily create mistrust. There are also short-term political gains to be had in creating mistrust of a larger neighbour. That is a common ploy when rulers, whether democrats or dictators, face problems at home. In Bangladesh, one of the two main parties describes itself as nationalist. The Bangladesh Nationalist Party leaves no one in any doubt that nationalism means constant awareness of the threat from India. The other major party in Bangladesh, the Awami League, in theory stands for mature relations with India, which are mutually beneficial. However, fear of being accused by its opponents of 'selling out' has meant that when in power the Awami League has likewise been extremely cautious in its dealings with New Delhi.

Tit-for-tat

This is not to say that India has played the role of big neighbour sensitively. When the Asian Development Bank annual meeting was held in Hyderabad in Andhra Pradesh, an economist involved in Southasian negotiations said to me, "India is very bad at downsizing with its neighbours, because of its lordly attitude." In many years of reporting on Southasia, I have not always been impressed by Indian diplomats' sympathy for their smaller neighbours. During my last trip to Bangladesh, I suggested to an Indian diplomat that allowing free entry of Bangladeshi goods without asking for reciprocity would not harm India's economy, and would greatly benefit its relations with the people of that country. He replied by reeling off a list of complaints about Bangladesh, suggesting that until Bangladesh behaved itself India could make no concessions. India's traditional attitude towards Nepal – including on the matter of trade-and-transit treaties, implied that its small neighbour could be a threat to the Indian economy. This did little to improve its reputation of being a good neighbour. I have always been saddened by India's tit-for-tat reaction to anything that has gone wrong in its relations with Pakistan. The spokespeople of the two countries vie with each other to make the most virulent, violent and verbose statements. In fairness, however, it has to be said that ever since the Bharatiya Janata Party-led coalition resumed its efforts to improve relations with Pakistan, the Indian government spokespeople have been more restrained.

It takes two to clap and two to quarrel, so all Southasian countries have to bear some blame for the paralysis that has afflicted and still does afflict Southasian cooperation. But the burden of removing the suspicion that causes this paralysis lies on India's shoulders. That will not just mean India being generous in trading with its neighbours and restraining its criticism of Pakistan. It will also mean making it absolutely clear that gone are the days of suspecting SAARC as an organisation created by the smaller neighbours to 'gang up' against India. Of course, the other hand also has to clap. The smaller countries must learn to trust India, and to reciprocate its generosity as well when exhibited. Their politicians will have to resist the tendency to arouse hostility to India as a distraction from their own failures.

I am not alone in suggesting that the burden of generosity lies on India's shoulders. Jagat Mehta has also written, "I would straightaway accept that the success or failure of South Asia's attempt to redeem its tryst with destiny rests overwhelmingly with India … India alone is in a position to orchestrate a turnabout from a climate of mistrust to one of positive underpinning of cooperation."

~ Mark Tully is a former Southasia bureau chief for the BBC World Service, with which he remains associated.