Valley versus hill

A week before two Naga boys – Chakho and Loshou – were killed by the paramilitary Manipur Police Commandos at Mao Gate, on the Manipur-Nagaland border; a week before 4000 people from Senapati District in Manipur were displaced from their homes to languish in makeshift camps, hospitals and homes of relatives around Nagaland; a week before Thuingaleng Muivah, the longtime Naga militant leader, attempted to visit his home village of Somdal, in Manipur; a week before 6 May 2010, when those two deaths started the recent flood of bottled-up sentiment in the Northeast – the signs of the Ibobi Singh-led Manipur government setting itself against a section of its own people were there for all to see.

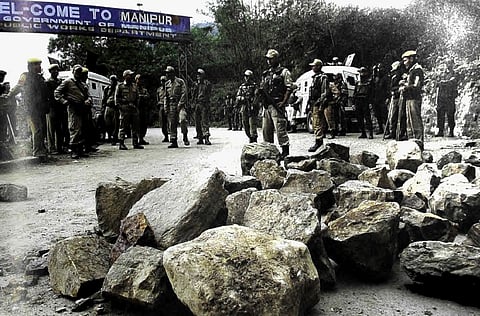

Since 12 April, the All Naga Students' Association of Manipur (ANSAM), along with a few other groups, had imposed an economic blockade on Manipur, in support of their demands regarding the Autonomous District Council (ADC) elections in the hill areas of Manipur (see accompanying article, 'Peoples under siege'). But from 5 pm on 2 May, after the Imphal government banned Muivah from entering the state, the government imposed Section 144, legislation prohibiting all gatherings in the hill districts of Manipur (where Manipur's Naga population is concentrated), and deployed extra security forces. It then went on to block the Mao Gate road – National Highway 39, the first point of entry from Nagaland into Manipur, prohibiting all vehicles from Nagaland and beyond from entering Manipur. Backed by armoured cars, advanced weaponry and bulletproof armour, paramilitary troops set up bunkers surrounding the Mao Gate area, rolled in boulders and locked down the road completely. In the event, Muivah stayed out.