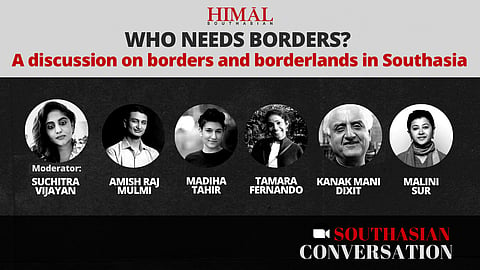

In this third edition of Southasian Conversation, a series of online crossborder discussions, we discuss how borders impact everyday lives in the margins, how they inflect conversations in the capitals and in national public spheres, and how people/ideas/economies manage to transcend physical borders despite their strict policing. So how have recent border skirmishes, cartographic tensions, and currents of orthodoxies of nationalism impacted the region and its people? And how might we reimagine territorial boundaries given, among other things, the unsettling changes posed by the climate crisis?

The question in the title – 'Who needs borders?' – is, therefore, both playful and serious. Southasians have, of course, learned to live with national borders. But exactly what kind of borders are we to have? Are the securitised and sometimes militarised regime of checkpoints the best we can have, or in the best interest of the region's people? Meanwhile, will movement and travel between the countries in the region continue to remain a costly, convoluted and, sometimes, dangerous affair? We might not all arrive at the same answers, but we at Himal feel the need to continually raise these questions.