HIMAL MEDIOCRITY SERIES – I

There is a well-known Southasian social scientist, a particular favourite of the editor of Himal, who describes himself on the jacket of a book as active in the environmental, human rights, alternative science and peace movements. Now I cannot say about the other three, but if this worthy is active in the environmental movement, then my name is Medha Patkar.

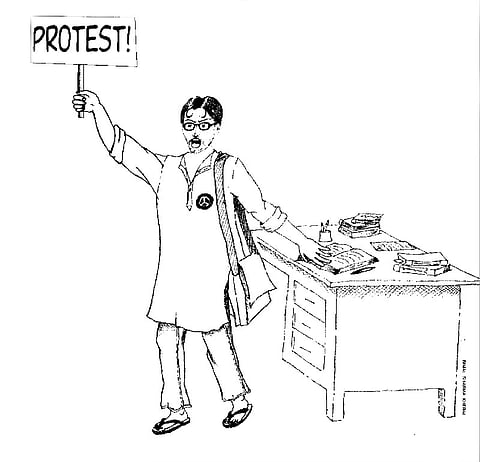

Exaggerated claims to a personal radicalism are the staple of Southasian social science, made with carefree abandon by man and woman, young and old, Nepali, Pakistani, Sri Lankan, Indian, Bangladeshi and (I dare say) Maldivian. It was once all right to label a piece of work in descriptive terms, that is, to label a study of land relations in eastern Nepal as, precisely, A Study of Land Relations in Eastern Nepal. Now it would be presented as An Action-Research Project or Programme of Participatory Intervention, written by an activist intellectual or intellectual activist.