Introducing the first edition of the Southasia Review of Books, a monthly newsletter that threads together our latest reviews and literary essays, curated reading suggestions on all things books-related from Himal’s extensive archive, as well as interviews with select writers and their reading recommendations.

Hello reader, and welcome to the first installment of the Southasia Review of Books newsletter! We at Himal hope that SARB will develop as an important space for all things books – contemporary and canonical, from across Southasia and beyond. You'll receive future installments of this newsletter, one on the last Sunday of each month. Write to us to share your thoughts and feedback.

On we go!

Our latest reviews from April:

First up this month, we have Kavitha Muralidharan's essay on Meena Kandasamy’s recent feminist intervention on the Tirukkural, the unparalleled and widely celebrated Tamil classic. Kavitha explores how an anti-colonial and feminist reimagining of the Tirukkural is long overdue – a text that has seen many translations and interpretations but, as Kavitha points out, very few of them attempted by women.

Take a look below for a special interview with Kavitha discussing the pioneering feminist voices of the Sangam era, classical Tamil literature in translation, plus reading recommendations.

In another piece from Himal’s pages this month, Dhanuka Bandara considers the work of Martin Wickramasinghe, a leading Sri Lankan writer of the 20th century, and Ananda Coomaraswamy, a key Sri Lankan cultural critic and philosopher, to uncover how agrarian utopianism came to be a fundamental part of Sri Lankan nationalist thought. Dhanuka writes on how this utopianism shines light on the country’s past, present and possible alternative futures. The idealised notion of the "village" – which was at the core of last year’s people’s struggle in Sri Lanka – can also be understood as part of this trend.

“If actively steering the economic life of millions of people is an apolitical activity, what else is political?” asks Sarath Pillai in his review essay of Nikhil Menon’s book Planning Democracy, a history of the entanglement of statistics, economic planning and democratic state-making in India. Sarath argues that while the book offers a comprehensive history of planning in India, what’s missing is a deeper analysis of the ways in which planning complicates aspects of Indian nationalist thought and history.

Interview with Kavitha Muralidharan + reading recommendations

On the back of Kavitha’s review essay on Meena Kandasamy’s path-breaking feminist translation of the Tirukkural, we spoke to her to learn more about the themes she raises in the piece.

Shwetha Srikanthan: Can you tell us about the presence or absence of women in early Tamil literature, both in terms of output and also representation?

Kavitha Muralidharan: The 1990s marked a significant era in the history of literature in terms of the voices of women. In the 1990s, women started writing about their bodies and desires in Tamil. This is not entirely surprising to those who are familiar with the history of the language – nearly a thousand years ago, we had women who wrote about their desires – but this does evoke some strong opposition. I remember a writer once calling for “burning the women writers who wrote so”. I also remember a rightwing co-panelist on a television debate rejecting my argument that the poet Andal of the Bhakti movement wrote erotic poetry in the 8th century. “Aren’t we civilised now?” he asked me.

Among the key Tamil women writers who heralded a new wave of writing is Salma, whose works are also known for their intimate portrayal of the lives of Muslim women, and the feminist poet Sukirtharani, whose poems are equally powerful in exposing caste and oppression.

There are several feminist publishing houses that focus on women’s writing in Tamil. I think the presence of women writers in Tamil Nadu today is not surprising considering that we have had at least forty women poets in the Sangam era.

I should also mention the Sri Lankan Tamil women poets like Selvi, Sivaramani, Anar and Sharmila Seyyid, who wrote so powerfully on war and living amid war.

SS: What makes the Sangam tradition distinct from other literary traditions across India and from subsequent eras?

KM: It is the presence of women poets that makes the Sangam distinct from other literary traditions. I remember an anthology of women poets from Kashmir who wrote between the 14th and 18th centuries. While I absolutely loved the poetry, the introduction called the presence of women poets in the 14th century a “rarity”. Avvaiyar would have perhaps said: “Hold my கள் [palm wine]”. For one, there were 40 women poets of the Sangam era who wrote some of the most significant verses of Tamil poetry that are still remembered today.

I am forever awed by the brilliance of Avvaiyar from the Sangam era. She wrote over fifty poems that find their presence in anthologies of Sangam literature such as Aganaanuru, Kurunthogai, Natrinai, and Puranaanuru. We have already spoken about one poem in the review (“Muttuven Kol”) which is also an expression of desire. There is another Puranaanuru poem of Avvaiyar, which I personally think is a forceful expression of her self-respect. The Sangam era had this practice of poets receiving gifts from the kings. Apparently, Avvaiyar was made to wait a while before the gatekeeper would allow her to receive this gift. She writes the poem to express her anger, asking: “Does the king Athiyaman Neduman Anji not know of his place or mine? Has the world become so poor that it cannot feed those with talent and popularity? I will get food in any direction I go.” I find this to be a powerful voice of a woman who demands recognition of her talent. That makes her and other Sangam women poets distinct.

After the Sangam tradition, Tamil literature had the Bhakti era. There are two notable women poets in Bhakti literature – Karaikal Ammaiyar and Andal. There are not so many women poets after the Bhakti era. One writer I would like to most definitely mention is Uthiranallur Nangai who wrote Paichalur Pathikam in the 15th century – arguably among the earliest examples of anti-caste literature in Tamil. “When thrown into the fire, sandalwood or neem wood emanates different scents. But when thrown into the fire, will a Brahmin or a Pulayar emanate different smells?” she writes. Legend has it that Nangai was thrown into the fire by her fellow villagers after she fell in love with a Brahmin who taught her the Vedas.

SS: In the review, you mention the Tamil Nadu Text Book Corporation’s plan to publish the entire corpus of Sangam literature. Could you tell us more about this and also the broader efforts of publishing houses in India to take a fresh look at other Tamil classical works?

KM: Translating and publishing the entire corpus of Sangam literature is a challenging task. But I am glad that the Tamil Nadu Text Book Corporation has taken it up and has a team of brilliant writers in place to do the work. I was told when I interviewed them last year that the project will take three more years. When Sangam literature in its entirety is published in English, it will perhaps provide the world with an opportunity to understand the Tamil literary landscape, and the rich history of Tamil language and literature better. There are of course some translations of Sangam poetry by A K Ramanujan, George Luzerne Hart and, more recently, M L Thangappa’s Love Stands Alone, edited by the historian A R Venkatachalapathy.

SS: As a translator yourself, what are some of the challenges you see of translating classical Tamil literature?

KM: What I really liked about the poet Isai’s interpretation of "Inpattuppal”, the Tirukkural’s third section, is that he brought in a touch of contemporariness. He followed a conversational style that sometimes held Thiruvalluvar [the author of the Tirukkural] in total awe and sometimes questioned why he had to repeat himself in poem after poem. This was beautiful in its own way, to see Thiruvalluvar as a companion sitting next to you and telling him what you think of his ancient verses. That is the beauty and magic of Tamil. The contemporariness employed by Isai came from Thiruvalluvar himself, and that is how I believe he remains universal.

Apart from that, the major challenge would be to find the right language to express the idea originally expressed by the author. I think it is especially difficult in the context of classical literature.

SS: Can you recommend other Tamil classics, already translated or in need of translation, that merit attention?

KM: I do think the women poets of the Sangam era need to be translated – not just for their antiquity but also to highlight that they had a voice and agency of their own and that they put it to effective use. Avvaiyar, Perungopendu and many other women poets expressed not just their desire but their anger too in Sangam literature. Uthiranallur Nangai had expressed her anger in Paichalur Pathikam. I think the anger of Tamil women writers needs to be translated as much as their desire should be.

Kavitha’s reading recommendations:

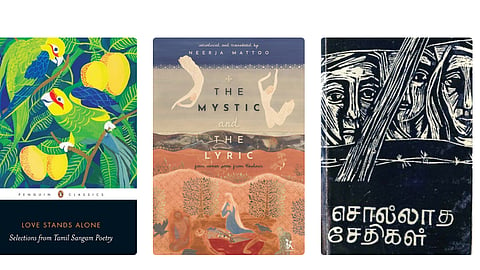

Love Stands Alone: Selections from Tamil Sangam Poetry by M L Thangappa. Edited by A R Venkatachalapathy. Penguin India (2010)

The Mystic and the Lyric: Four Women Poets from Kashmir. Translated and Edited by Neerja Mattoo. Zubaan Books (2019)

Sollatha Seithigal [Unspoken Messages] An anthology of Sri Lankan Tamil women Poets. Edited by Chithiraleka Mounaguru (1986)

Thank you for reading the Southasia Review of Books. Questions, comments, feedback? Feel free to write to me at shwethas@himamag.com.

Until next time!

Shwetha Srikanthan

Assistant Editor, Himal Southasian