📚 Southasia Review of Books - September 2023

The Southasia Review of Books is a monthly newsletter that threads together our latest reviews and literary essays, curated reading suggestions on all things books-related from Himal’s extensive archive, as well as interviews with select writers and their reading recommendations.

You’ll receive installments of this newsletter on the last Sunday of each month. If you would like to manage your Himal newsletter preferences, please click here. Write to us to share your thoughts and feedback.

Hello reader

Welcome to another edition of the Southasia Review of Books!

This month, Jatin Gulati looks at shifting lens-based visual practices in the variously partitioned Subcontinent. In his review essay on Unframed: Discovering Image Practices in South Asia, edited by Rahaab Allana, Jatin discusses how various artists, collectives, exhibitions and visual practices from the region confront the divided realities of Southasia, yet also point to the region’s entanglements.

“Unfixing any singular narrative of post-colonial Southasia, the book works through disarrayed notes on the Subcontinent that still point to commonalities, hope and solidarity,” Jatin writes, “These notes address moments etched in our conscience through generational memory, while still very much narrating our present contexts.”

This sentiment is also captured in a photo essay we published this month. The photographer Graciela Magnoni documents her journey through the Punjab in both India and Pakistan, showing a land and a people still connected despite Partition and the militarised border between them.

Graciela points out the striking similarities between the images she took on the Pakistani and Indian sides, and how it is often impossible to tell which side is which. This shaped the idea for her book Watan: Homeland Punjab, published in 2021, compiling images that bridge the two sides of the Punjab.

In another essay from Himal’s pages this month, Namrata Raju reviews Seema Alavi’s Sovereigns of the Sea: Omani Ambition in the Age of Empire. Looking at the histories of Omani sultans and drawing on her own experiences as a Southasian growing up in Oman, Namrata details the fluid forms of nationhood and identity that have linked Southasia and West Asia for generations.

Filling historical gaps for those interested in Oman, Zanzibar and Southasia, Sovereigns of the Sea is an important addition to the growing collection of writing on Indian Ocean history. As Namrata writes, “Narrating these histories through the lens of the sultans and the Indian Ocean, Seema Alavi’s book leaves readers pondering whether today’s borders will ever adequately explain who we are now and whence we came.”

Take a look below for a special interview with Namrata, plus her recommendations for further reading.

Interview with Namrata Raju on how Southasia and Oman intertwined

Shwetha Srikanthan: In the review, you write about the ways in which the lives of Southasians and West Asians have been connected for generations. Could you tell us about the present-day impact of this on both regions?

Namrata Raju: Given my work on migration, I often assess matters primarily via the lens of the movement of people. Even today, Oman, the wider Arab Gulf and Southasia witness the widespread movement of people in multiple ways. While Southasians may emigrate to West Asia in search of employment, movement in the reverse often occurs as well, albeit for different reasons. These may range from seeking educational opportunities in Southasia, to taking an ailing relative to a medical specialist. Medical tourism often works in the reverse, with many travellers from the Arab Gulf coming into Southasia to seek treatment. The movement of people for generations into the present day also means that there are several things innate in our everyday lives that in fact, hail from elsewhere. Akin to samosas and sambusak, the reverse often happens with chai: karak chai or what we more popularly refer to as masala chai in Southasia can be ubiquitous in several Gulf states – and its origins are of course, in this region.

SS: You also note that Sovereigns of the Sea is particularly compelling in that it fills historical gaps for those interested in the story of Oman, Zanzibar and Southasia. However, there are also obstacles to accessing research materials, for example on the Omani side. What can readers looking for these stories do to understand places where information is sparse?

NR: My scuba diving instructor in Oman once told me that even on the same dive, every diver has a different view of the sea, since they are each swimming at a specific depth and in a particular part of the ocean. If we are to be discerning readers, we must first consider this. From which specific part of the ocean, and from whose perspective, is the author telling a story? It is imperative for us as readers to keep this at the back of our minds, with whatever we choose to read.

Second, I believe it is important for us to always diversify what we read. Over the past ten years, I have made it a point to read up on translated works I may have missed since such volumes of literature come out of Southasia each year which are in languages other than English. Most of my reading during this period has also been on authors from across the Global South and minority groups, because it occurred to me one day: why have I not read as much literature from Nigeria? Or from Uganda? Plenty of tremendous literature is out there, and I believe it is on us to make the effort: my life has only been enriched by it. This similarly extends to books from the Arab Gulf, all it takes is redirecting ten minutes from Instagram to look for books by authors from the region. A few books that are probably quite easy to come by for readers are Warda: A novel by Sonallah Ibrahim; and Jokha Alharthi’s books, Celestial Bodies and Bitter Orange Tree.

SS: West Asia-bound migration remains an important avenue for Southasians in search of employment. Are there any parallels between the slave trade and migration across the Indian Ocean historically and exploitative systems of migrant labour in the Arab Gulf today?

NR: Around the world, migration is a vessel for multiple wins if done right. On the one hand, emigrants can pursue sandcastle dreams of sending their kids to college, or someday buying a plot of land back home; and on the other, migration aids the economic development of the two countries involved. Migrants buttress the economies of the states to which they emigrate and often tend to remit large sums of their income home as well. As a researcher on labour and migration, every piece of work that I have ever done has reiterated one point: that migration can accrue monumental benefits to states, industry and workers if – and this is a big “if” – facilitated safely. Have we ever pondered over what we would do without the food of emigrants? Sans the movement of people, we would not have access to burritos in the United States, masala dosas outside of South India, or Korean fried chicken anywhere else in the world – and we would be much the poorer for it. With the movement of people and increased labour mobility also comes the mass sharing of cultures.

I would extend the same argument to Oman and the wider Arab Gulf. Although the exploitation of workers, particularly low-wage emigrants, many of whom are Southasian, remains rampant, we must lobby for the safe migration of workers. Instead of pushing to shut down migration, which would have massively deleterious implications for both, states and people, we should look to build economies premised on what we call “decent work” for both migrants and citizens. Oman and the other five Gulf states continue to have the Kafala system in place; essentially an employer-tied visa sponsorship system, weighted in favour of the employer and exploitative of workers in policy and practice. While recent years have seen some reforms to this system in varying degrees and on different fronts across the region, labour rights organisations underscore that the ground realities of workers remain unchanged. Some of the most egregious problems that workers face continue to be wage theft, racial discrimination and debt bondage from paying illegal recruitment fees, all within a complete vacuum of freedom of association.

Despite these remarkably worrisome circumstances, I would not liken the plight of today’s workers to 1800s Oman. This would defenestrate centuries of socio-economic development, multiple shifts in political paradigms, and above all the evolution of the global discourse on worker rights. I am also a firm believer that we must look ahead instead of so far behind. Should we be comparing worker precarity now to the 1800s, or should we instead aspire towards what worker lives should look like in 2050 and beyond? Should this type of migrant worker precarity be acceptable anywhere in the world? Why does more than half of the global population still not have social protection in 2023, is that not utterly shameful?

Namrata Raju’s reading recommendations for notable works on crossborder identities

One of my favourite books on layered identities and migrants in the Arab Gulf is Jasmine Days by Benyamin, translated by Shahnaz Habib. A work of fiction premised on real-life events, the book describes events surrounding the Arab Spring. Recounted from the vantage point of a young Pakistani woman in an unnamed Gulf country (likely Bahrain), it also touches upon matters of identity, movement and political upheaval with nuance and grace.

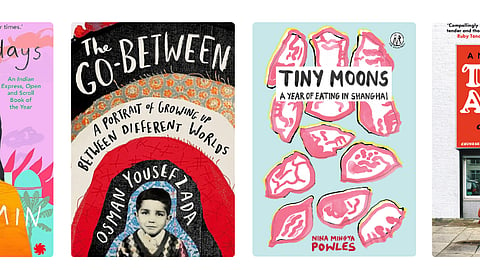

The second book I would recommend is the one that I am currently halfway through: The Go-between by Osman Yousefzada. This book is a memoir of Yousefzada’s life as a Pakistani immigrant in the UK in the 80s, rife with racial tensions. Migrant struggles such as cultural assimilation and grappling with social conservatism are set against colourful anecdotes about a child coming of age during a particularly racially charged period in British history.

The final two books I would recommend are perhaps some of my favourites from my past year, since they blend together a love for food with a search for identity. I read Tiny Moons: A Year of Eating in Shanghai by Nina Mingya Powles in one sitting, it is also a teaspoon-sized book. Powles hails from New Zealand, and the book is about her reconnecting with her Chinese identity via food. You can learn a great deal about Chinese food and culture through this book, perhaps the only downside being that it leaves you with a strong hankering for dumplings.

Takeaway: Stories from a Childhood Behind the Counter by Angela Hui, was my other favourite from 2023. This book is a memoir, speaking to Hui’s life in a small Welsh town as part of a Chinese immigrant family, that had to leave on the heels of the Cultural Revolution. What makes this particularly compelling is that Chinese takeaway is something many of us in urban spaces around the world have seen, and this book makes you feel like you are sitting behind the counter instead of ordering food to take away. While Hui describes her tussles with identity, racism and family matters throughout her childhood, she also describes how her family expresses love through food. Her book is interspersed with a variety of recipes, perhaps as a means to convey love to her family despite the emotional turmoil.

This month in Southasian publishing

Especially over the last decade, there have been several notable literary translations into English from Southasian languages, proving that some of the region’s best literature has been and continues to be written in what are often called “vernacular” tongues. Yet there’s still a long way to go in terms of wider visibility, demand and appreciation for these works.

Here at Himal’s editing desk, a slate of new translations from the Southasian publishing sphere caught our eye this month:

The feminist writer and activist Taslima Nasrin’s Burning Roses in My Garden, translated from the Bangla by Jesse Waters, is her first-ever collection of poetry in translation. This made us revisit Elen Turner’s profile of Nasrin in the Himal archives, unravelling the mythology and persona of the writer.

Naulakhi Kothi by the Pakistani novelist Ali Akbar Natiq, translated from the Urdu by Naima Rashid, is a story set in the Punjab in the years leading up to Partition and through to the 1980s.

The Greatest Punjabi Stories Ever Told, edited by Renuka Singh and Balbir Madhopuri, covers short fiction by four generations of Punjabi writers, including Gurbaksh Singh, Balwant Gargi and Amrita Pritam, Jatinder Singh Hans and more.

Another collaborative project is For Now, It Is Night, a selection of the Kashmiri writer Hari Krishna Kaul’s stories, translated into English for the very first time by Kalpana Raina, Tanveer Ajsi, Gowhar Fazili and Gowhar Yaqoob.

Sandalwood Soap and Other Stories, translated by Kavitha Muralidharan, is a new collection of works by one of India’s most well-known literary writers, Perumal Murugan, exploring rural life and caste in Tamil Nadu. We hope to bring you a deep dive into Murugan’s oeuvre in a forthcoming long-form essay. Watch this space.

For more on caste and Tamil literature, read Ashik Kahina’s essay on the Tamil writer Pandiyakannan, the first novelist from the Kuravar community, and his novel Salavaan – an intimate portrait of the lives of manual scavengers and their relationship to the state.

This month, the Booker Prize has announced the six novels on its 2023 shortlist, featuring one Indian-origin author Chetna Maroo. Her shortlisted debut novel, Western Lane, follows a young squash prodigy from a Gujarati immigrant family in 1980s London, exploring adolescence, sisterhood and grief – much like the two older novels also worth your attention, Somebody Loves You by Mona Arshi and Gifted by Nikita Lalwani.

September also marks the publication of Descent into Paradise by Daniel Bosley, documenting his work as a journalist and editor at a local news outlet in the Maldives. In his reporting on the country’s volatile political landscape, its struggles for justice its reckoning with climate change and more, Bosley exposes the gaps between the Maldives’ pristine image as a tourist destination and the fragile realities of life on its islands.

Take a look at some of Bosley’s writing on the Maldives in the Himal archives here, and keep an eye out on our website and next month’s edition of this newsletter for an excerpt from the book.

Until next time, happy reading!

Shwetha Srikanthan

Assistant Editor, Himal Southasian