Of scholarship and politics: the relentless pursuit

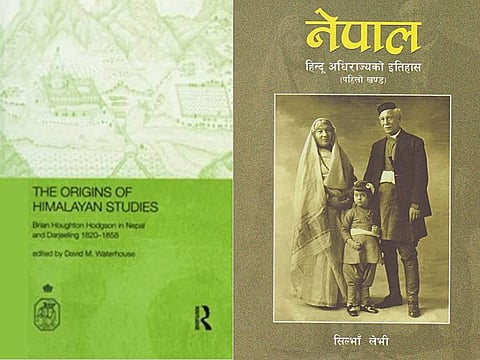

The origins of Himalayan studies, Brian Houghton Hodgson in Nepal and Darjeeling. 1820-1858. David M Waterhouse London and New York Routlege Curzon( 2005).

Nepal: Hindu Adhirajyako Itihas (Pahtto Khand) Sylvain Levi Translation: Dilli Raj Upreti Patan: Himal Books (2005).

Those of us who have devoted much of our careers to the study of the societies and cultures of Nepal have contributed unconsciously, perhaps inevitably, to the notion that there is a group of works, written mostly in English, that form an indispensable canon dealing with that country. One thinks immediately of names such as Colonel William Kirkpatrick, Francis Buchanan Hamilton, Brian Hodgson, H A Oldfield, Daniel Wright, Perceval Landon and, of course, Sylvain Levi, the greatest of French Indologists. There are certainly others, and each can form his own.

Canonicity struggles against analysis and criticism. It is there to conceal, as much as it can, the politics of scholarship. The unread quickly becomes the unquestioned. To maintain its authority, the canon is occasionally plundered for individual facts, like the price of salt or musk in l829. Rarely, however, is it subjected to critical scrutiny. Like the gods, it floats in midair, above us all, its divine status taken for granted. But one has only to take a desultory look at, say, the complexities of English surgeon Daniel Wright's History of Nepal to get a sense of the human politics that surround this famous work, and to realise that its very structure derives from the politics of the British Residence, its divine status highly dubious.

The two works under review here relate directly to these problems of politics and scholarship. The Origin of Himalayan Studies is a volume of essays about Brian Hodgson, the first British Resident in the Kathmandu Valley and a significant supplier of some of the first Nepali manuscripts to reach Europe. The second, Nepal: Hindu Adhirajyako Itihas, is a Nepali translation of the first volume of Levi's celebrated Le Nepal: Etude Historique D'Un Royaume Hindou (Nepal: A Historical Study of a Hindu Kingdom).

Vice President of the Royal Asiatic Society, David Waterhouse's volume consists of 12 articles describing Hodgson's work from Kathmandu and, later, Darjeeling. Significant new material is brought to light here, and the breadth of Hodgson's interests is shown more clearly than ever before. US professor Thomas Trautmann introduces the volume with an interesting foreword that, among other things, highlights the misfortunes of Hodgson's long life. This is followed by sketches of Hodgson himself; his political role and domestic problems; his relationship with Joseph Hooker, the English botanist; and essays on Hodgson's many studies – Buddhism, Buddhist architecture, zoology, mammals, ornithology, ethnography and linguistics. The book is beautifully and profusely illustrated with drawings by artists that Hodgson had employed in both Nepal and Darjeeling.

Still, despite the detailed nature of the book, one would have liked more about Hodgson's education, as well as his relationship to Thomas Malthus, Charles Darwin and other major figures of the 19th century, including the chief Indologists of his time. Also, what were his working relationships with his "native informants" and assistants? How well did Hodgson know any of the languages of Nepal? More about such things may not be possible, however, as the record may simply not be available.

My main criticism is that The Origin of Himalayan Studies is a bit too celebratory of Hodgson. There is little reference to those crucial figures – like Newar scholars Amritananda and Ram Singh – who made possible his fame in the 19th century. There is little on Hodgson's attitudes towards imperialism and colonialism. Surely, in such a volume as this, there was room for a discussion of Hodgson's essay on the suitability of the Himalaya for colonisation – the mountains being, according to him, a natural habitat for development by 200,000 stalwart Anglo-Saxon hearts.

One of the books contributors, US professor Donald Lopez, is quite correct when he notes that Hodgson was more of a collector than a scholar. Except for inscriptions and other archaeological remains, he collected everything. Indeed, Hodgson was a cladistical maniac, a relentless classifier, a genius of taxonomy and even taxidermy – but not an intellect that analysed and interpreted. Little of his writing is very extensive. Many of his papers are very short, only two or three pages, and few topics are developed beyond their initial presentation. His broader ideas remain unexpressed. He wrote no books, translated or edited nothing. By these comments I do not wish to diminish his achievements, but at this juncture it is best to be clear. As ongoing surveys of Hodgson's papers in the British Library reach completion, we may soon know more about his methodologies. At this point, however, we must see him mostly as an enabler of others.

In Nepali again

Of the writers mentioned above as canonical, all except Sylvain Levi were Englishmen in the service of the East India Company or the British government. In contrast, Levi (1863-1935) spent his entire career as a professor at the Sorbonne in Paris. It was not an ordinary career, and Levi was no ordinary mind. By general consensus he was the leading India scholar of his time, and one of the masters of both Indian history and the texts on which that history is based. Almost everything he wrote still deserves the attention of the scholarly world.

At the suggestion of the French philosopher Ernest Renan, Levi began the study of Sanskrit as a young man under Abel Bergaigne, a teacher to whom Levi was completely devoted. Bergaigne held the chairs of both Indo-European philology and Sanskrit at the Sorbonne, and most of his work was dedicated to Vedic literature. When he died in l890, Levi succeeded him to both chairs. Well aware of the controversies surrounding the Veda, Levi chose to devote much of his career to the study of the later periods of Indian history, in particular the history of Buddhism. He was far more interested in how Indian civilisation shaped the cultures of Asia – Nepal, Sri Lanka, Burma and Southeast Asia, Tibet, China, Japan and Mongolia. He chose not too follow the other route, the one that led to the attempt by much of European Indology to view early ancient Indian history as also the earliest part of European history – a problem with which Indian studies are still contending today.

Undaunted by the size of his task, Levi mastered Chinese, Japanese and other languages necessary to his work. He began extensive travels. In l898, he made the first of three trips to the Subcontinent, and it was during this time that he also visited Nepal, which, as he said on numerable occasions, was his second patrie, or fatherland. He became enamoured of the Kathmandu Valley, and after three months of intense work that year, he returned to Paris with enough material to produce his longest and most famous work, Le Nepal, three volumes published from 1905 to 1908.

By now, Le Nepal is in many respects out of date. Much has been done in archaeology, anthropology, epigraphy (the study of inscriptions) and history of which Levi could never have guessed. He knew of only 17 Sanskrit inscriptions of the Licchavi period, for instance, while today there are over 200 now known. Still, Le Nepal bristles with ideas and insights, dazzling suggestive sparks that make one pause at the country's fortune in having such a brilliant chronicler.

Despite its importance, because it was written in French, the book has remained unread in Nepal. While an English version is available, for the first time Nepalis now have the opportunity to read this important text in their own language. Longtime resident in France, translator Dilli Raj Upreti has rendered Levi's French into clear and relatively simple Nepali. While the translation is excellent, the text, particularly the notes, is marred by many orthographic errors and typographical mistakes. These should be removed from future editions and from the two volumes yet to appear. One awaits the dosro and tesro volumes with enthusiasm.

We do not know whether Hodgson and Levi ever met, although they could easily have done so in the early 1890s. They would have had much to discuss. Both were deeply humanistic but relentless in the pursuit of their quarries, even forcing their wills on a resistant government in Kathmandu. Like Hodgson, Levi was no slouch when it came to collecting. The story of how he demanded the excavation of the Manadeva pillar at the famed Changu Narayan temple – to the great anger of the priests – is told by him in his carnet de sejour, his journal. In Waterhouse's volume, brief reference is also made to an instance in which a potential language informant that Hodgson wished to interview was finally delivered to him in a cage by the Nepali authorities.

Neither Levi nor Hodgson could have been well understood by their Nepali hosts. The ultimate disposition of their collections would have been found amusing, if not ridiculous, or even horrifying.

Several years ago, this reviewer accompanied a young Nepali woman who was visiting the US for the first time to the American Museum of Natural History. As we roamed the halls, we were subjected to an endless, undifferentiated mass of displays and glass cases. We moved from stuffed birds to stuffed mammals to dioramas of peoples of the world. As she gazed at these last exhibits, she cried out, "Did they have to kill the people too?"

I still do not think I have an answer to her question.