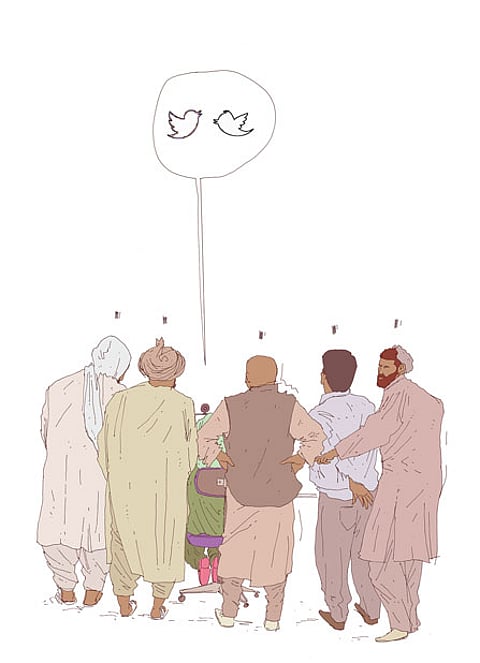

Online identities; unfolding realities

On International Women's Day 2013, a group of women's rights activists in Kabul called Young Women for Change saw no better way to mark the occasion than to open the first female-only internet café in Kabul. Young women needed a place to surf the internet in peace, they argued, without facing the harassment they often endured in regular male-dominated cafés. For the growing numbers of urban, educated youth in Afghanistan, as in most other parts of the world, life without the internet is now unimaginable. Like people everywhere, they use it for entertainment and information; to stay in touch with far-flung friends and family members; to pursue personal projects including education, self-expression and love; and for social activism and political mobilisation. Researchers who study the internet are increasingly coming to terms with the fact that far from being the radical, liberating force that some feared and others celebrated in its early days, the internet can actually be quite conservative: it often reproduces many of the conventional behaviours and social hierarchies that are found offline. But my research on the Afghan diaspora has convinced me that when it is harnessed at a time of intense social flux and transition, as in Afghanistan today, the internet can also have disproportionate cultural and political effects.

Banned under the Taliban, internet use has exploded in Afghanistan in just over a decade, reaching a million users in 2009, and doubling to two million by 2013, according to the Ministry of Communication and Information. While this figure represents just six per cent of a largely illiterate population, projects to close the digital gap are intensifying as a fibre optic network is developed by Chinese investors, with a three-fold drop in price announced in 2013 and further reductions expected. The number of Facebook users in Afghanistan has jumped from 6,000 in 2008 to 470,000 in 2013, and most people get online at internet cafes or via their mobile phones. In fact, my ambitious young friends told me, one of the perks of a good government or international NGO job was reliable, steady access to the internet.

A favourite pastime is sharing images and Youtube video clips on Facebook or via mobile phones, and the commentary under these is often a barometer for public opinion on a variety of topics. People express both national solidarity and hatred and distrust of rival ethnic groups or political factions. They also have heated exchanges about sexual propriety and the public role of women, as evidenced by the commentary about Ariana Saeed, a Swiss-raised pop singer who was the boldest female contestant to date on the hit reality show Afghan Star (the Pop Idol-like televised music competition that has taken the country by storm), appearing in figure-hugging clothes and without a headscarf. The mudslinging was to be expected, but more surprising perhaps was the extent of support for Ariana, with comments to the effect that her talent was what really mattered, and should be a source of pride for all Afghans.

The political impact of the internet is illustrated by the very different treatment of a document of considerable public interest in 1989 and in 2013. In 1989, the government of the then-president Najibullah was seeking to distance itself from the crimes of the early years of the communist regime. It released the names of 11,000 people who had disappeared without a trace, but which it now admitted with 'deep regret' had been killed by the state security agency between 1978 and 1979. The list was handed over in Kabul to the British politician and human rights campaigner Lord Nicholas Bethell. Although Lord Bethell then passed the names on to the Afghan rebel leaders based in Peshawar, the diaspora at the time was fragmented ethnically, geographically and politically, and had limited means of communication. Over subsequent years of political upheaval the list was forgotten and the families of many victims, were left waiting in a cruel limbo for news of their loved ones.

Two decades later, in the process of investigating the asylum application of a former Afghan security officer, the Dutch police unearthed a version of this list containing just under 5000 names in the hands of an elderly Afghan widow living in Germany. On 18 September 2013, the Afghan daily newspaper Hasth-e-Subh (8am) published the list in print and online. This time, however, the news spread like wildfire throughout Afghanistan and its diaspora as people posted the article to their social media networks. The tension was palpable as many of my Afghan Facebook friends in Europe and North America discovered the list and pored over it nervously. One by one, several of them posted about the dreadful moment they found the names they were looking for, and the mingled sense of pain and relief at finally knowing the truth after 35 years. People commiserated and shared condolences, poems and remembrances on Facebook. They also began planning long-overdue memorial services: 500 Afghan-Americans attended an event in Fremont, California in October, and under significant public pressure, two days of national mourning were declared in Afghanistan at the end of September. This was an unusual moment of national unity in grief and renewed calls for justice and accountability for the crimes of decades of political conflict and war – a reckoning with the past that has been suppressed under the Karzai administration, in which former warlords have attained powerful positions thanks to an amnesty law. The wide publicity given to the list, and the ability of people to verify the death of their loved ones for themselves and pass the news on quickly, marked a form of political immediacy that had not been possible in an earlier era.

Political mobilisation on a global scale

Afghans have also used the internet to respond to contemporary atrocities. On a cold winter day in February 2013, I visited a group of around 40 Hazara men, women and children as they sat wrapped in blankets opposite the Houses of Parliament in London. They were protesting the bombing of a market in Quetta, Pakistan, that had killed at least 91 of their brethren and wounded 190 more. It was the second day of their three-day sit-in and many had braved the freezing temperatures and the rain overnight. Alongside graphic images of the victims' bloodied bodies, a small sign read: "Our dear ones in Quetta must know that we are not only shedding tears for them, but we are defending them with our bodies and souls." Written in Dari, this sign was clearly intended to be broadcast via social media to their fellow protesters in Quetta and around the world.

This protest was part of a larger wave of Hazara political and cultural activism around the world that is attempting to tackle their disadvantaged position in many of the countries in which they live. Historically known as the most downtrodden ethnic group of Afghanistan, the majority of Hazaras are Twelver Shia, originating in the mountainous Hazarajat region of central Afghanistan. In the last century, millions of Hazaras have become refugees or migrant workers for reasons of poverty compounded by brutal repressions.

In the days following the attack, the volume of online responses to it among the Hazara community was hard to miss. Thanks to social media, within minutes Hazaras across Pakistan, Afghanistan, and the rest of the world were planning parallel protests and making heartfelt statements of support. Facebook was a crucial tool for spontaneously sharing news of the attacks (including graphic photographs and videos), information about protests and outpourings of grief, support and solidarity. Hazara activists shared news and photographs from protests across Pakistan and Afghanistan, several European and Australian cities, in front of the CNN headquarters in Atlanta, Georgia, at the UN office in New Delhi, and outside the Canadian Parliament in Ottawa.

At the London protest, Khadija Abbasi, an activist and postgraduate student of anthropology, described the pivotal role played by the internet in mobilising the protesters.

She told me:

Most people had their mobile phones out and had Facebook up and running. They were in contact with other Hazara groups throughout Europe and even in Quetta – messages were being sent back and forth, video clips were being posted on Facebook from Quetta, people were looking at them, and they were encouraged to continue. When they saw that thousands of people were out there [in Quetta] in the cold weather, even small children, they said – why shouldn't we be able to endure the cold? Through these websites and Facebook, they can be in contact much more easily, more comfortably and more inexpensively. In my opinion, [the internet] plays an incredibly crucial role. People have been deriving energy from each other.

The internet also encouraged more creative responses. In Kabul, a fresh-faced young Hazara musician called Abbas Neshat posted a video clip on his Facebook wall with a new song he had recorded in the Hazaregi dialect. Neshat plays the dambura, a long-necked lute, and sings Hazara folk songs. A popular contestant on Afghan Star, Neshat has over 3,000 friends and followers on Facebook, hundreds of whom had ‘liked’, shared and commented on the song within days of its posting.

My soul-brother, my martyred sister, lovely as a flower

Your crimson blood is the standard-bearer of our hope

You will go down in history as honourable and noble

Faithful to peace and true to your word

With the blood of these martyrs

You have rooted out ignorance and deception

The oppressor has been degraded and humbled by you

The flowing river has become a stream of blood

By the grace of the crimson blood of the innocents

The enemy’s regime and his palace have been overthrown.

(Translated from colloquial Hazaregi with help from Khadija Abbasi.)

Although Hazaras mobilised throughout the world on the basis of their ethnicity, inside Afghanistan Hazara activists took care to build bridges and use more inclusive rhetoric. Hafizullah Shariati, a poet, linguist and university lecturer and one of the organisers of a hunger strike and sit-in in Kabul, appealed on Facebook to all of his friends of various ethnic backgrounds to support the strike, with the words: “Terrorists have come to our house, and your house is not far from ours.” He later noted with satisfaction that supporters from most ethnic groups had come to encourage the protesters, including several prominent politicians. Many ordinary Afghans of all ethnicities also expressed their support through social media, reflecting the fact that in Afghanistan, educated urban dwellers in particular recognise the need to put ethnic fragmentation behind them and build a common Afghan identity.

Looking for love online

Perhaps the most revolutionary effect of the internet is playing out at a far more individual level. New communication technologies are playing an important role in allowing young people to communicate and get to know each other, independently of the family-based networks that usually decide who can interact and who can marry. Ten years ago when I was doing fieldwork in Afghan refugee communities in Iran, instant messaging was all the rage. Young people would try to get each other’s ‘ID’ (email address or user name) and then email and chat with one other online, whether using dial-up modems at home or the increasingly ubiquitous kafi-nets (internet cafes). It was just as often young women as men who initiated such contacts, and they facilitated the creation of extensive networks of educated young people across various cities in Iran, Afghanistan and in the diaspora all around the world. More recently, however, Facebook has become the most popular way for people to get to know each other, with people sometimes adding hundreds of individuals as friends whom they have never met and have no prior connection to. Facebook is increasingly being used by young people seeking love and marriage partners. While young men are little concerned with online security, young women take greater precautions, rarely posting their own photographs (a favourite substitute is pictures of Bollywood actresses). While some such relationships end in marriage, in other cases online deception leads to heartbreak, as many female profiles turn out to be fakes set up by other men.

One such love story that I saw unfold was, fortunately, genuine and had a happy ending. Fatimah was a headstrong, ambitious young woman and a poet whom I met while working with an Afghan refugee cultural organisation in Iran. In the peculiar combination that has emerged in post-revolutionary Iran, she was both a deeply pious Muslim and an outspoken feminist. Passionate about literature and full of ideas for projects to improve the lives of her compatriots, she did not expect to marry. “Afghan men want a wife for cooking, cleaning and bearing children, not for progress. I knew that with my personality I would not be able to tolerate a life of slavery and servility,” she told me. She was editing a poetry anthology and looking for sponsors to help publish it, and somehow ended up chatting on Yahoo Messenger to a friend of a friend, Abbas, a student of mathematics who had grown up as a refugee in Pakistan but had recently sought asylum in France. He politely declined to sponsor her book, but they started chatting regularly. For almost two years they just chatted about the news, Afghan culture, and current affairs, but gradually the bond between them deepened and they fell in love. Fatimah was extremely cautious, having heard many stories of internet trickery. She kept Abbas secret so that nobody would gossip about her, and she kept him hanging on until she was absolutely sure she could trust him.

She told him her family would never accept him because they were from different ethnic groups. Undeterred, he went to Pakistan to first seek his parents’ blessing, and then travelled to Iran to meet her. When Fatimah realised he was coming, she hastily told her parents about him. Her mother and siblings were supportive, but her father initially opposed the match because Abbas was an unknown quantity. Abbas had to go to her house several times to talk to her family and formally ask for her hand. Eventually, her father assented, because he found Abbas to be a kind and decent young man, and because years living in Iran had blurred the ethnic distinctions that dominated marriage considerations in Afghanistan. But Fatimah still had to be careful. She didn’t tell anyone outside her immediate family and a few close friends about him until they were legally married. “What we did was contrary to tradition in a traditional society: a struggle against ethnic prejudice. And I wanted to be the decision-maker in my own life. Usually girls don’t have the right to choose in Afghan traditional society, and that’s why I kept quiet. If I’d said something, we would have been harassed. My other relatives weren’t happy and they still aren’t; they wanted to break our union. But I don’t care at all. My family is important; they love me and support me. The others don’t matter.”

It took another three years for the visa formalities to be sorted out, and in that time Fatimah and Abbas communicated online every day. “Oh, what nights we had when we chatted [via instant messaging] till dawn! Abbas always phoned me, and after our marriage he called every day, as well as chatting all night. We chatted so much that my parents were amazed at the phone bill, as in those days our internet connection was through our phone line. I wrote a lot of poems. I had beautiful emotions. When we got engaged, I dedicated a number of poems to him. Our love was not like in a Bollywood film where it starts with a single glance; our love came from knowing each other, from understanding each other. And now we’re very content. I have a very deep feeling of happiness.”

For idealistic young people of an intellectual bent like Fatimah and Abbas, the will to support each other in making a contribution to their homeland and their people has become a highly desirable quality in a life partner. I heard many sad stories in Afghanistan about talented and educated young women whose husbands insisted that they put aside their creative activities or work outside the home after marriage, so as not to damage their honour, and who suffered violence if they tried to resist. So doubtful was Fatimah of her ability to find someone who would permit her more than a life of “slavery and servility” that at first she did not want to marry at all. The internet helped her find and get to know Abbas half a world away: a companion who admired her precisely for her ambitions and encouraged her to study, continue her poetry and her activities on behalf of Afghan refugees. For young Afghan intellectuals, love marriage has become a patriotic project in the name of progress, greater rights for women, and ultimately a healthier society, and the internet is providing a venue for them to meet and put these ideals into practice. Abbas called the fact that young people were now marrying for love a ‘revolution,’ a ‘radical’ act, and explicitly associated it with modernity. His two older sisters in Quetta had agreed to let their parents choose their husbands for them, but his two unmarried younger sisters were “armed with technology,” as he put it, and like him were busy looking for love online. Time will tell whether the collective political action or the individual self-expression will be the more significant social change brought about by new communication technologies in Afghanistan. For now, educated young Afghans, whether in their own country or in refugee communities around the world, will keep building their networks and sharing their ideas, opinions and most intimate feelings online. When Fatimah gave birth to a premature baby girl in November last year, it was only natural that she should express her hopes and fears in verse – and share the poem on Facebook:

Life on the third floor of the hospital,

Room 11.1,

a root of sickness slowly growing,

a cold room with warm nurses.

That rainy day

children who had died

gathered around my baby

and I was afraid.

A white grave had come alive behind the door of the room,

and I kept swatting away the flies

and the cacophonous everyday noises from my baby’s ears.

I thought of the native lullabies of my people,

of my mother,

and her many births, one after the other.

Life went on in the rain

on the other side of my window

and time’s cardiogram unravelled as normal.

All my worries

had fallen asleep quietly in a corner,

and I slowly dissolved myself

in a cup of bitter coffee.

Zuzanna Olszewska is a lecturer in social anthropology at the University of Oxford. She specialises in the ethnography, cultural history and poetry of Iran and Afghanistan, and is currently working on a project on social media, identity and nation-building in the Afghan diaspora.