The almost-forgotten – and still unpunished – ministerial attack on journalists at Sri Lanka Rupavahini Corporation

This story is published in collaboration with the Free Media Movement of Sri Lanka, part of a series for Black January, which commemorates crimes against Sri Lanka's journalists. It has been translated and edited from Sinhala, with updates on T M G Chandrasekara’s case.

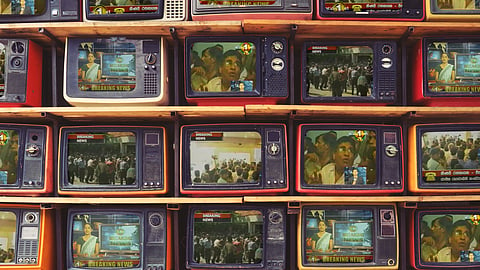

“This morning, a group of thugs led by Mervyn Silva forcibly entered the [Sri Lanka Rupavani Corporation] news division and assaulted News Director T M G Chandrasekara.”

On 27 December 2007, this was the breaking news reported by every television channel in Sri Lanka, referring to the violent intrusion into the state-owned television broadcaster, Sri Lanka Rupavahini Corporation (SLRC), by a group led by Mervyn Silva, then the labour minister.

At the time, the United People’s Freedom Alliance coalition government, led by Mahinda Rajapaksa as president, had been in power for just over three years. Silva’s intrusion into the premises of Rupavahini, and the chaos that ensued, was broadcast live across all private television networks. The assault on Chandrasekara sparked nationwide outrage. Yet while this event was widely discussed during the early years of Rajapaksa’s first term, public discourse surrounding it had significantly diminished by the time his second term began in 2010.

This decline can be attributed to two key reasons. First, the media community, already intimidated by acts of violence, was subjected to an even more brutal reality of forced disappearances and assassinations that escalated after 2007. Second, Chandrasekara, a veteran journalist, chose to seek justice through legal channels rather than media activism. Despite ample evidence, including eyewitness accounts and video footage, the investigation into the assault stagnated, and the attorney general’s department remained conspicuously silent for years, which many saw as deliberate inaction. In January 2008, a government committee appointed to investigate Silva’s conduct promised to release a report in two weeks, but failed to follow through.

This reveals the impunity around attacks on media institutions in Sri Lanka – even when the institution in question is state-owned. It also exposes the extent to which state-owned media in Sri Lanka are expected to uncritically amplify government narratives.

PUBLIC DISCOURSE on this long-forgotten incident was rekindled in August 2022, when the Criminal Investigation Department (CID) arrested Silva in connection with the case. Given that 18 years have now passed, and that the incident never gained the same level of sustained media attention as other attacks on journalists – including the killing of Lasantha Wickrematunge, the editor of the Sunday Leader, or the abduction of the media rights campaigner Poddala Jayantha – revisiting this incident remains necessary.

At the time of the storming of Rupavahini, the Rajapaksa administration was facing internal challenges to its political dominance. This was most publicised through the fallout between Rajapaksa and the former foreign minister Mangala Samaraweera, who had been instrumental in bringing Rajapaksa to power but later emerged as one of his fiercest political opponents. As a result, Samaraweera became a primary target for vitriol from government ministers.

One such verbal attack occurred at the inauguration of the Mahanama Samaraweera Bridge in Matara, named after Mangala Samaraweera’s father, a minister in the government of S W R D Bandaranaike in the 1950s. Held on 26 December 2007, just one day before the assault on Chandrasekara, the event set the stage for what unfolded at Rupavahini the next day.

In May 2016, nearly a decade after the incident, Silva recounted the event in an interview published in the Sinhala-language newspaper Lankadeepa. The conversation is not only revealing about the assault but also about Silva’s role as a minister within Mahinda Rajapaksa’s government:

Journalist: “Like the Sinhala proverb about the woodpecker that pecked at a banana tree, you carried out political contracts for powerful leaders. But when it came to the attack at the national broadcaster, didn’t you learn an unforgettable lesson?”

Mervyn Silva: “That’s an old story. But yes, it was a good lesson for me. That was a contract given to me by Mahinda Rajapaksa. When I was with the leader, I did whatever he asked. While we were on our way to inaugurate the Mahanama Samaraweera Bridge in Matara, Mahinda Rajapaksa told me that the staff at the national broadcaster were still loyal to Mangala Samaraweera. He asked me to ‘look into it’. Even at the bridge opening, he assigned me another contract – he told me to insult Mangala Samaraweera in my speech. I did more than that. Today, I regret it. His mother must have been hurt by what I said. I attacked the entire Samaraweera family. But if I were to speak to Mangala now, I would tell him: I was not a traitor to you – I merely carried out Mahinda Rajapaksa’s orders.

When I returned, I went to the national broadcaster, not to pick a fight, but to deliver another message. I was sent there by Mahinda Rajapaksa himself, who had called the station beforehand and ordered, ‘Mervyn is coming – beat him up’. That is the Rajapaksa style. I walked into a trap. I carried out contracts for the Rajapaksas, but in the end, I was the one who got hit.”